北朝筆記 vol.8 北齊貼團花帶蓋綠釉文壺探究,對比常盤山文庫:松心閣「蓮心千古」南北朝特別展覽 - A Northern Qi Cover Jar from the Northern & Southern Dynasties Exhibition, in Comparison with Tokiwayama Bunko.

- SACA

- Jun 2, 2024

- 22 min read

Updated: Oct 1, 2024

點評:存世量稀少,神秘用途值得探索(存世其他作品有金粉、金箔附著於內壁),帶蓋或為首見。

這件作品尺寸巨大,帶蓋高42cm,是南北朝收藏中不可缺少的一件。對比飽受追捧,裝飾繁複的蓮花尊,這件作品以內斂的線條和低調的造型為美,在綻放的北朝時代,這種向內而生的精神內涵往往容易被短暫忽略。

本品與常盤山文庫的收藏屬於同種類型,但將其放置於世界僅存的10件同類作品中看,可以推測這類作品的年代上限應該是北朝,下限應該是唐代(鑑於兩件作品來自唐代發掘記錄)。

不同時期主要的不同在於:1. 釉色; 2. 貼塑的造型、數量、排列方式; 3. 胎土的顏色(白,或是偏紅); 製作工藝,如是否系切(線割)的方式等等。

綜合考量,這件作品應該比常盤山文庫所定的隋代更早,應該是北朝時代的作品。從造型上,更接近根津美術館的藏品。(https://www.nezu-muse.or.jp/sp/collection/detail.php?id=41360)

Comment: A rare survivor, its mysterious funtionality is worth exploring (other surviving pieces have gold dust and gold leaf attached to the interior), the only jar with a cover.

This is a huge piece, 42cm in height with lid, and is an indispensable piece in any Northern or Southern dynasty collection. The present work is of the same type as that in the Tokiwayama Bunko collection, but when placed in the context of the only ten surviving works of this type in the world, it can be surmised that the upper dating limit of this type of work would be the Northern Dynasties, and the lower limit would be the Tang dynasty (given that two of the works are from late Tang excavation records).

The main differences between the different periods are: 1) the colour of the glaze, earlier pieces are more pale and bright; 2) the shape, number, and arrangement of the stickers; 3) the colour of the clay (white being earlier, or reddish sui or later); and the workmanship, such as whether or not it was cut (wire-cut) using the peddle coil method.

nezu museum collection.

Taken together, this work is probably earlier than the Sui dynasty, which is earlier than the Tokiwayama Bunko, and probably dates from the Northern Qi Dynasties. In terms of form, it is closer to the Nezu Museum's collection, which is dated to the Norhtern Qi dynasty. (https://www.nezu-muse.or.jp/sp/collection/detail.php?id=41360)

以下是SACA學會的專文:

目前全世界範圍內有十件貼團花文壺,其中九件绿釉,一件素胎,年代上限是北齊,下限是唐代。偏向北齊的只有兩件,北齊至隋的有四件,隋代一件,唐代三件。除了兩件出自河北,其他分布世界各地:常盤山文庫、波士頓美術館、大都會博物館、弗利爾美術館(2件)、根津美術館等。

常盤山文庫在「北齊的陶瓷」一書中作過詳細的論述,本文將圍繞這個主題,討論北齊陶瓷的審美和工藝。

本文是对SACA學會2022年发表的《北齐之光:璀璨时代的陶瓷之美 - Northern Qi, the Diversity and Subtlety of Arts》的更新,更新內容:大都會博物館、塞努奇博物館、私人藏品的對比內容。

這個時期,產生了兼容性極強的文化,並造就了隋唐時代恢弘大氣、兼收並蓄的文明;這個時期,將西域、草原與中原緊密地聯繫在一起,從而對北中國的版圖有了重新的勾畫;這個時期,通過戰爭、改制,將遊牧部族與中原漢人的關係進行了全面的調整,並使"文化"超越種族,形成古代中國鮮明的文明特徵。可以說,沒有十六國北朝,就不會有空前強盛的隋唐,更不會有生命力極強的中國文化。

There are currently ten of these bottles in the world, nine in green glaze and one without glaze, with an upper date range of the Northern Qi dynasty and a lower date range of the Tang dynasty. There are only two that favour the Northern Qi, four from the Northern Qi to Sui, one from the Sui dynasty, and three from the Tang. All but two are from Hebei, and the others are from all over the world: the Tokiwayama Bunko Japan, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Freer Gallery (two), and the Nezu Museum of Art, and one in Private Collection.

The Tokiwayama Bunko has written a detailed discussion of the ceramics of the Northern Qi, and this article discusses the aesthetics and craftsmanship of Northern Qi ceramics in the context of this theme.

This article is an update of the SACA's 2022 publication, ‘Northern Qi, the Diversity and Subtlety of Arts,’ with comparisons between the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Senucci Museum, and private collections.

This period gave rise to a highly compatible culture and a magnificent, eclectic civilisation of the Sui and Tang dynasties; it linked the Western regions, the steppes, and the Central Plains together, thus redrawing the map of Northern China; it was a period when the relationship between the nomadic tribes and the Han Chinese in the Central Plains was comprehensively restructured through wars and reforms, and ‘culture’ transcended race to form a distinctive civilisational feature of Ancient China. It also enabled ‘culture’ to transcend race, forming a distinctive feature of civilisation in Ancient China. It can be said that without the Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern Dynasties, there would not have been the unprecedentedly powerful Sui and Tang dynasties, not to mention the vitality of Chinese culture.

一、綠釉貼團花文壺 隋 常盤山文庫 藏 / Tokiwayama Bunko Collection, Minamiaoyama, Tokyo Japan.

二、綠釉貼團花文壺 北齊 根津美術館 藏 / Nezu Museum Collection, Tokyo, Japan.

三、綠釉貼團花文壺 北齊 私人 藏 / Private Collection.

四、綠釉貼團花文壺 北齊 - 隋 弗利爾博物館 藏 / Freer Gallery, DC.

五、綠釉貼團花文壺 北齊 - 隋 弗利爾博物館 藏 / Freer Gallery DC.

六、綠釉貼團花文壺 北齊 - 隋 大都會博物館 藏 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

七、綠釉貼團花文壺 北齊 - 隋 賽努奇博物館 藏 / Cernuschi Museum of Art, Paris.

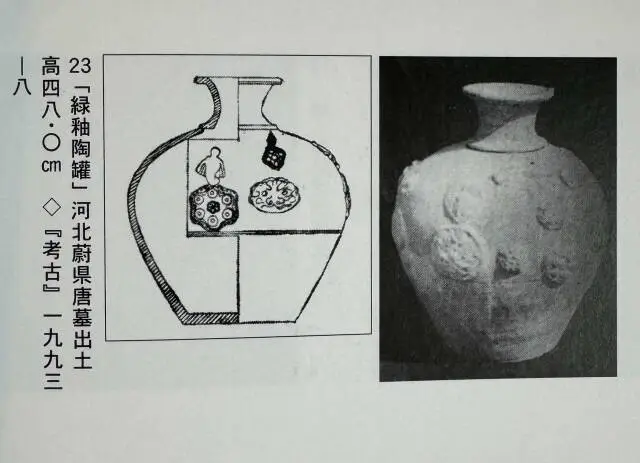

八、绿釉貼團花文壺 唐代 河北蔚县 出 / Weixian Tang Tomb, Hebei

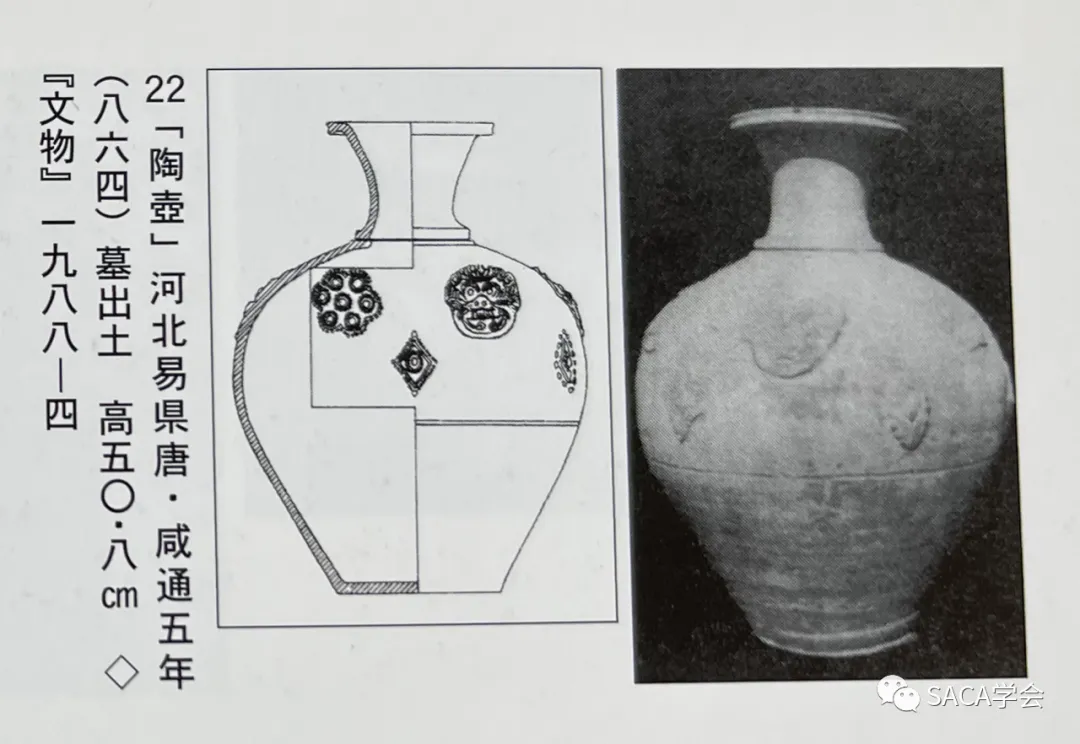

九、素胎貼團花文壺 唐代 河北易县 出 / Yixian Tang Tomb 864AD., Hebei

十、绿釉貼團花文壺 唐代 繭山龍泉堂 展覽 / Mayuyama Ryusendo, Tokyo.

常盤山文庫綠釉貼團花文壺

Jar with Applied Design Covered with Copper-Green Lead Glaze

Sui dynasty 隋

H. 39.8 cm, MD. 12.0-16.7 cm, BD. 18.5 cm, Wt 7,900g

This large jar with green lead glaze has thick, prominently applied decorations which make the jar appear massive. Traces of paddling are apparent on the lower part of the body and the string cut mark appears on the foot, indicating that this jar was built in the coil and paddle method, with finishing on the potter’s wheel. The unglazed base shows a rather reddish body clay (pl.7b). The mouth rim area has a broad and slightly protruding band.

这只施有绿色铅釉的大壶有厚厚的、突出的贴花装饰,使整体看起来壮硕。壶身下部有明显的拉胚痕迹,壶足有割泥线的痕迹,说明此壶是用泥条与泥板的方法制作的,并在陶轮上进行了精加工。未上釉的底部显露出相当红的胎土(pl.7b)。口沿区域有一条宽且略微突出的圈。

The applied decorations seem to be part of a carefully planned arrangement, given the incised lines that circle the body from upper to lower sections, thus marking the position for each applied decorations. The shoulder of the jar is decorated with an alternating application of three thick, flower-like motifs (fig.19 p.55) and three beast faces (fig.26 p.58). The flower-like motifs are composed of eight rounds are surrounded by small beaded dots and are much more massive than any of the other applied decorations on this jar. The beast face motifs seem flat in comparison to these massive flower-like motifs. The second band of decoration is made up of cross motifs composed of five rounds surrounded by beads (pl.7) and flower motifs consisting of six slender petals (fig.20 p.55). The latter motif cannot be found on any of the comparative materials mentioned later in this article. Jewel-like applied decorations and lugs are interspersed among these motifs.

这些贴花装饰似乎是精心策划的一部分,由自上到下环绕壶身的弦纹标明每个贴花的位置。壶肩的贴花装饰是由三个厚重的花形图案(图19第55页)和三个兽面图案(图26第58页)相互交替。花形图案由八个圆形组成,环绕小珠点,比此壶的其他贴花装饰都要大得多。

与这些巨大的花形图案相比,兽面图案显得很平淡。第二条装饰带是由五个圆形珠子组成的十字架图案(pl.7)和由六片细长花瓣组成的花朵图案(fig.20 p.55)组成。后一种图案在本文后面提到的任何对比材料上都没有发现。在这些图案中还穿插有宝石状的贴花装饰及系耳。

Some reddish extraneous material appears on the green glaze at the grooves of these applied decorations. This might be pigment or glue. Chemical analysis indicates that it might be some form of plant sap, but the minute size of the sample precludes specification. A similar reddish extraneous material was found in the hollows on the top of rounds that make up the flower-like motifs. It is not certain whether this material was original to the work, or whether it was some later addition. We might imagine that this material was used to attach jewels, precious stones or gold to the jar at some point during the intervening centuries since its creation. It is interesting to note that a tiny section of gold leaf was found in the jar (pl.7a), though it is not certain whether it is related to the reddish extraneous material.

在这些贴花装饰的凹陷处,绿色的釉面上出现了一些淡红色的外来物质。这可能是颜料或胶。化学分析表明可能是某种形式的植物汁液,但由于样本尺寸很小而无法确定。

在构成花形图案的圆形顶部的空洞中也发现了类似的淡红色外来物质。目前还不能确定这种材料是器物的原始材料,还是后来添加的。我们可以猜想这种材料是在壶完成后的几个世纪中的某个时间点,用来固定珠宝、宝石或黄金的。

值得注意的是,壶内发现了一小段金箔(pl.7a),尽管不能确定它是否与红色的外来物质有关。

Until two recent finds in Hebei, it had been many years since examples like the Tokiwayama jar with its elaborate applied decoration had been excavated. First, in 1988, an unglazed jar with motifs like those found on the Tokiwayama work was reported at a tomb dated to 864 in the late Tang dynasty (fig.22 p.56). The jar has a long flaring neck similar to the vessel shape of a jar in the Freer Gallery (pl.13b) discussed below. The jar has flower-like motifs composed of seven rounds surrounded by beads, a decorative form also seen on the Freer jar and a jar in Boston (pl.13e), but different from the Tokiwayama. Though judging only from the photograph and figure in the excavation report (Wenwu, 1988-4), the motifs on the 864 jar seem to be absolutely flat as compared to the thick and massive motifs of the Tokiwayama jar.

直到最近两次在河北有新发现之前,已经有很多年没有出土过像常盘山壶这样具有精致的贴花装饰的例子了。

首先,1988年在一座年代为864年的晚唐墓中发现了一件素胎壶,上面有类似于常盘山壶的图案(图22第56页)。该壶有一个长长的喇叭口,与下面将讨论的来自弗利尔美术馆的一件壶(pl.13b)器型相似。

壶上的花纹由七个圆形的珠子围绕而成,这种装饰形式也见于弗利尔壶和波士顿的一件壶(pl.13e),但与常盘山壶不同。虽然仅从发掘报告(《文物》,1988年4月)中的照片和数据来看,年代为864年的壶的图案与常盘山壶厚重的图案相比,似乎是绝对的平面图案。

Another example was excavated in 1993 from an undated late Tang dynasty tomb (fig.23 p.56). The shape is the same as the 864 jar from Hebei and the Freer jar. This jar is reported to be green glazed (Kaogu 1993-8), while the 864 jar is unglazed. The applied motifs are arranged in no particular pattern or symmetry. These applied decorations are as flat as those on the 864 jar from Hebei.

另一个例子(图23第56页)是1993年从一个未定日期的晚唐墓中出土。器型与河北的864壶和弗利尔壶相同。据报道,该壶施以绿釉(《考古》,1993年8月),而864罐子是素烧未施釉的。其贴花图案的排列没有特别的模式或对称性。这些贴花装饰和河北864壶上的装饰一样,都是平面的。

Given these excavated materials, scholars have begun to advocate a possible Tang date for the wares with these shared design methods and motifs. And yet, even though I have only seen photographs and report sketches for these excavated works, it seems that these late Tang examples differ from the Tokiwayama jar. The Tokiwayama jar is characterized by massive applied decorations such as the flower-like motifs on the shoulder (fig.19 p.55), while the decorations on the excavated examples are flat. The three-dimensional quality of the Tokiwayama jar decoration is reminiscent of the massive showy decorative style of lead glazed wares from Shanxi province in the Northern Qi dynasty, while the flatness of the excavated examples is akin to the flatness of the mould-applied decoration found on Tang Sancai. Similarly the excavated examples lack of sense of volume in their shape and the tautness found in the Tokiwayama jar’s proportions.

In addition to the excavated materials discussed above, there are several examples which share motifs with the Tokiwayama jar. These examples include a jar in the Nezu Museum in Tokyo (pl.13a), two jars in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington (pls.14bc), a jar in the Musée Cernuschi in Paris (pl.13d) and a jar in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (pl.13e). All of these works are green glazed jars with some common decorative motifs. Their shapes, however, differ, and each has its own distinctive mood and atmosphere. Some are tautly formed, others lack this sense of tension. With the exception of the Nezu jar, I have not yet an opportunity to closely examine these examples, and thus simply work from my observation of their photographs and information provided by their respective museums.

鉴于这些出土材料,学者们开始主张这些具有相同设计方法和图案的器物可能来自唐代。然而,尽管我只看到这些出土器物的照片和报告草图,这些晚唐的例子似乎与常盘山壶不同。

常盘山壶的特点是有大量的贴花装饰,如肩部的花纹(图19,第55页),而出土的例子上的装饰是平面的。常盘山壶装饰的立体感让人联想到山西省出土的北齐时期铅釉器上大量炫耀性装饰风格,而出土例子的平面性则类似于唐三彩上模印装饰的平面性。同样地,出土例子在器型上缺乏体积感,也没有常盘山壶在比例上的紧绷感。

除了上面讨论的出土材料外,还有几个例子与常盘山壶的装饰图案相同。这些例子包括东京根津美术馆一件(pl.13a)、华盛顿弗利尔博物馆两件(pl.14bc)、巴黎塞努奇博物馆一件(pl.13d)以及波士顿美术博物馆一件壶(pl.13e),最后是新增的大都会博物馆一件,和私人收藏一件。

这些器物均为有着相同装饰图案的绿釉壶。然而,它们的器型各不相同,每一件都带有独特的气质和感觉。有的造型紧绷,有的则缺乏这种紧张感。除了根津壶之外,我还没有机会详细观测这些例子,因此仅通过它们的照片和各自博物馆提供的信息进行观察。

Among these other examples, the Nezu jar (pl.13a) seems to be the closest to the Tokiwayama jar, and yet, the whole impression of the Nezu jar’s body is quite different from that of the massive Tokiwayama jar. The Nezu jar does not present such a solid appearance as that of the Tokieayama jar. The Nezu jar also lacks the incised circling lines marking the position of applied decorations on the body, as found on the Tokiwayama jar. Two kinds of flower-like motifs appear on the Nezu jar. The motif type found on the lower part of the body is massive in form and composed of eight rounds surrounded by beads. The motif type found on the upper part of the body are composed of seven rounds each surrounded by beaded dots and these motifs are flatter than those on the lower part of the jar. The former motif is the same as that on the Tokiwayama jar (fig.19 p.55) and the latter is unique among these cited examples. The Nezu jar’s base bears the cutting string mark (fig.24 p.57). The clay is less reddish than that of the Tokiwayama jar. Tiny traces of gold powder were found inside the Nezu jar, though it is not known whether this is linked to the gold found in the Tokiwayama jar. It is fascinating to note, however, that traces of gold — powder in the case of the Nezu jar and leaf in the case of the Tokiwayama jar — were found on these jars.

在这些例子中,根津壶(pl.13a)似乎是最接近常盘山壶的,然而,根津壶壶身的整体印象与巨大的常盘山壶截然不同。根津壶并不像常盘山壶那样呈现出坚实的外观。

根津壶也没有像常盘山壶那样在壶身上刻画弦纹来标明贴花装饰的位置。根津壶上出现了两种花形图案。壶身下部的图案巨大,由八个圆形的珠子环绕而成。壶身上部的图案由七个圆圈组成,每个圆圈周围有珠点,这些图案比壶身下部的图案更平坦。

前者与常盘山壶(图19第55页)上的图案相同,后者是这些例子中独一无二的。根津壶的底部有割泥线的印记(图24 p.57)。

胎土泛红程度相比常盘山壶更少。在根津壶内发现了微小的金粉痕迹,尽管不知道这是否与常盘山壶内发现的黄金有关。然而在这些壶内发现黄金的痕迹十分令人惊叹,其中根津壶是金粉而常盘山壶是金箔。

The jar in the Freer Gallery of Art, which entered the gallery collection in 1930, has a long flaring neck, while the Tokiwayama and Nezu jars have broad bands on their rim and no neck. This long, flaring neck shape is also found on the two excavated examples from Hebei province. According to the photograph supplied by the Freer, there is no string cut mark on the base of the Freer jar (fig.25 p.57). The Freer jar shares the use of a jewel-like motif and lugs with that of the Tokiwaya. The flower-like flat motif composed of seven rounds is also found on another Freer jar, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston jar and the excavated examples from Hebei. The beast face motif (fig.27 p.58) is quite different from the found on the Tokiwayama jar (fig.26 p.58), as it has a ring in its mouth and is surrounded by beaded dots.

来自弗利尔美术馆的壶是1930年进入其收藏序列的,它有一个长长的喇叭口,而常盘山和根津的壶在其口沿处呈宽带状,没有颈。这种长长的喇叭口形状也出现在河北省出土的两个例子中。根据弗利尔美术馆提供的照片,弗利尔壶的底部没有割泥线的痕迹(图25第57页)。

弗利尔壶与常盘山壶共同使用了类似珠宝的图案和耳。由七个圆形组成的花形平面图案也出现在另一件弗利尔壶、波士顿美术馆的壶和河北出土的例子中。兽面纹(图27,第58页)与常盘山壶(图26,第58页)上的兽面纹截然不同,它的嘴里有一个环,周围有珠状的小点。

Another jar in the Freer Gallery of Art (pl.13c) has the oldest provenance among these examples, namely it was part of the Charles Lang Freer bequest in 1906. The jar is simply decorated with its sole motif decoration flower-like flat motifs on an incised line circling the shoulder. The shape of the mouth also differs from the others mentioned above. According to information provided by the Freer Gallery of Art, the base has a string cut mark.

弗利尔美术馆的另一件壶(pl.13c)在这些例子中出处最为古老,它是1906年查尔斯·朗·弗利尔遗赠的一部分。

此壶的装饰很简单,唯一的图案是环绕肩部的弦纹上的花状平面图案。口沿形状也与上述其他壶不同。根据弗利尔美术馆提供的信息,底座上有割泥线的痕迹。

弗利尔博物馆 藏

The jar in the Musée Cernuschi (pl13d) is also simply decorated. The only motif on this jar is the cross-shaped motif also found on the Tokiwayama jar, which is composed of five rounds surrounded by beads. This motif is only found on Tokiwayama jar.

来自巴黎塞努奇博物馆的壶(pl13d)的装饰也很简单。此壶唯一的图案是在常盘山壶亦有发现的十字形图案,由五个圆形的珠子围成。这个图案仅在常盘山壶上出现过。底足的做法略有不同,没有系切纹。

塞努奇博物馆 藏

The Boston jar (pl.13e) does not have as finished an impression as the other jars. Though each of the applied motifs can also be found on the other examples mentioned above, their arrangement is somewhat rougher in handling. While the motifs are applied to the other jars with some consideration of arrangement, the Boston jar is decorated with various motifs in no particular order. This type of unordered design can also be found on the examples from the late Tang tombs in Hebei province (fig.23 p.56). Flower-like motifs composed of seven rounds surrounded by beaded dots found on the Boston jar are also seen on the other examples, except those at the Nezu and Tokiwayama. The Boston jar displays the jewel-like motifs also found on the Nezu and Tokiwayama jars.

波士顿壶(pl.13e)看起来不像其他壶那样是一件完成品。尽管其每一个贴花图案也可以在上述其他例子上找到,但在布局处理上有些粗糙。其他壶上的图案排列都有一定的考虑,而波士顿壶上的各种图案却没有特定的排列顺序。

这种无序的设计也可以在河北晚唐墓葬的例子中找到(图23,页56)。波士顿壶上发现的由七个圆点包围的花形图案在其他例子中也能看到,除了根津壶和常盘山胡。波士顿壶上同样也发现了根津和常盘山壶类似的宝石状图案。

The several examples with motifs like those found on the Tokiwayama jar all lack uniformity in their handling, clay and vessel shape. Given such differences, it does not seem possible to date all of these examples to the Tang dynasty simply on the basis of the fact that these motifs are the same as those found on works excavated from Tang tombs. Rather, the excavated examples from the late Tang dynasty seem to be the last stage of this type of jar and it seems better to allow a certain latitude in the matter of dating of the other examples mentioned above.

这几件在图案上类似常盘山壶的例子,在排布、胎土和器型上都缺乏统一性。鉴于这些差异,似乎不可能仅凭这些图案与唐代墓葬出土的器物相同,就把所有这些例子的年代均定为唐代。相反,晚唐时期出土的例子似乎是这种类型的壶的最后阶段,在上述其他例子的年代问题上,似乎最好允许一定的自由度。

In terms of the dating of the Tokiwayama Jar, its orderly arrangement of applied motifs and the systematic usage of incised lines to govern that motif distribution, seem to indicate the methodical production of an early design stage. Further, the jar has two types of applied decoration, namely, the thick and massive type of decoration found in the flower-like motifs composed of eight rounds (fig.19 p.55) and cross shaped motifs whose voluminous impression is similar to the decoration of vases from the tomb of Lou Rui 娄叡 (pl.9d), and the flat type as seen in the jewel-like motifs, beast face motifs (fig.26 p.58) and flower shaped motifs with six petals (fig.20 p.55), whose flatness is similar to the decoration of the jars reported from the late Tang dynasty tombs. A logical design progression would seem to suppose first a design with two types of decoration later simplifying into a design with just flat decoration, but current materials do not allow confirmation of this hypothesis.

就常盘山壶的年代而言,其有序排列的贴花图案和系统地使用弦纹来控制图案的分布,似乎表明早期设计时有条不紊的生产。此外,该壶有两种类型的装饰:厚重且巨大的装饰类型,包括由八个圆形组成的花形图案(图19第55页)和十字形图案(其丰满的印象与娄叡墓中发现的花瓶装饰相似,如图9d);以及扁平的装饰类型则,包括宝石状纹饰、兽面纹(图26第58页)和六瓣花形纹(图20第55页),其扁平程度与晚唐墓葬中报告的壶装饰相似。从设计的逻辑发展来看,似乎首先是有两种装饰的设计,后来简化为只有平面装饰的设计,但目前的材料不足以证实这一假设。

Given a comparison with the examples listed above, the Sui dynasty might be considered a more concrete date for the Tokiwayama jar. I propose a Sui dynasty date based on the following points. The Tokiwayama jar recalls the massive applied decoration found on lead glazed wares produced in Shanxi province during the Northern Qi dynasty, those large-scale Northern Qi dynasty wares are not deliberately green-glazed wares, but rather were wares with transparent lead glaze with a green or yellow tinge. Similarly, the Norhtern Qi dynasty wares display a very white clay, quite unlike the reddish clay. The green glaze found on small works from the Northern Qi dynasty is light and bright in tone, and thus differs from that on the Tokiwayama jar. Given these factors, it would be difficult to date the Tokiwayama jar to the Northern Qi dynasty. Further, according to the Compilation (p.128), the applied decoration was not yet popular in the Northern Wei dynasty and a survey of datable materials makes it difficult to date the jar to a pre-Northern Qi dynasty period. On the other hand, in spite of the presence of the examples from the late Tang tombs, the taut tension of the Tokiwayama jar makes it hard to date it to Tang Dynasty. I also believe that the voluminous impression of the jar’s applied decoration differs from that produced during the Tang Dynasty. Thus, through a comparison with known extant examples and given present understanding of wares from these periods, a Sui date seems appropriate for the Tokiwayama jar. Hopefully as excavations continue, further material will come to light in the future which will allow a confirmation of this proposed dating.

小结:

一、绿釉贴团花文壶这个品类的年底上限应该是在北齐,下限是唐代。

二、年代较早没有颈部的文壶,分别有三件:常盘山文库(隋)、根津美术馆(北齐)、私人藏(北齐)。除了两件河北唐代出,其他作品更严谨的定代可能是北齐至隋。

三、根据常盘山文库的研究,常盘山文库之所以没有定为北齐是因为胎的颜色偏红,而北齐时代的偏灰白。

四、釉色的质感、流动性,早期的与晚期的不同。早期更为浅色和明亮。

此外:

鉴于与上述例子的比较,常盘山壶更有可能断代为隋代。根据以下几点提出隋代的判断。常盘山壶让人想起北齐时期山西省生产的铅釉器物上存在的大量贴花装饰,那些大型的北齐时期器物不是刻意的绿釉器物,而是带有绿色或黄色调的透明铅釉器物。

同样,北齐时期的器物也显露出非常白的胎土,与泛红色的胎土完全不同。在北齐时期的小型器物上发现的绿釉是浅色和明亮的色调,因此与常盘山壶的绿釉不同。鉴于这些因素,很难将常盘山壶的年代定为北齐时期。此外,根据《汇编》(p.128),在北魏时期贴花装饰还没有流行起来,对可考证材料进行调查后,很难将该壶断代为北齐之前的时期。

In Conclusion:

First, the upper limit of the end of the year for the category of green-glazed, appliquéd clerical jugs would have been in the Northern Qi dynasty, and the lower limit in the Tang dynasty.

Secondly, there are three earlier dated Wen pots without necks: Tokiwayma Bunko (Sui), Nezu Museum of Art (Northern Qi), and private collection (Northern Qi). With the exception of two from the Tang dynasty in Hebei, a more rigorous dating of the other pieces is likely to be from the Northern Qi to Sui.

Third, according to research by the Tokyiwayama Bunko, the reason why Tokiwayama Bunko did not date it to the Northern Qi is because the colour of the body clay is reddish, whereas that of the Northern Qi period is greyish-white.

Fourth, the texture and fluidity of the glaze colours are different between the early and late periods. The early ones are more light-coloured and bright.

In addition:

Given the comparison with the above examples, it is more likely that the Tokiwayama pots will be dated to the Sui dynasty. A Sui dynasty judgement is proposed on the basis of the following points. Tokiwayama pots are reminiscent of the extensive appliqué decoration present on lead-glazed wares produced in Shanxi province during the Northern Qi period, and those large Northern Qi period wares are not deliberately green-glazed, but rather transparent lead-glazed wares with a greenish or yellowish tint.

Similarly, Northern Qi wares reveal a very white clay, quite different from the reddish clay. The green glaze found on smaller wares from the Northern Qi period is of a lighter and brighter hue, and therefore different from that found on Changpanzan pots. In view of these factors, it is difficult to date Changpanshan pots to the Northern Qi period. In addition, according to the Compendium (p. 128), appliqué decoration was not yet in vogue during the Northern Wei period, and it is difficult to date the pot to a period prior to the Northern Qi period after investigating the datable material.

私人藏的带盖文壶更有可能是北齐的制品。胎色偏白,系切法也符合早期的做法。年代更偏向北齐。底的做法更接近根津美术馆壶,系切的同时,带有三支钉痕,与北齐时代的底足制作一致。

带盖则存世仅见,盖钮的做法与隋唐后期的做法不同。特别是盖钮并没有居中,而是设计在一边,形成十分特殊的视觉冲击。盖钮的设计值得继续研究。

由于在根津的文壶里发现金粉,在常盘山文库文壶里发现金箔,并且在常盘山文库文壶的外壁发现红色遗留物,被认定为固定金银珠宝的胶水,可以推测这类早期罐的作品的储存与功能金银珠宝密切相关,有可能是佛教密切相关的器物。

It is more likely that the private collection of covered pots is a product of the Northern Qi period. The white colour of the body and the method of lacing and cutting are consistent with earlier practice. The date is more in favour of the Northern Qi period. The base is similar to that of the Nezu Museum of Fine Arts, and the lacing, along with the three nail marks, is consistent with a foot made in the Northern Qi period.

The lid is the only surviving example, and the style of the lid and knob is different from that of the late Sui and Tang dynasties. In particular, the knob is not centred, but designed to be on one side, creating a very special visual impact. The design of the lid is worthy of further study.

Since gold dust has been found in Nezu's Jar, gold foil has been found in the Tokiwayama Bunko, and red remnants have been found on the outside of the Tokiwayama Bunko, identified as glue for fixing gold and silver jewellery, it is possible to speculate that the storage of these early pots was closely related to the functioning of gold and silver jewellery, and that they may have been artefacts closely related to Buddhism.

另一方面,尽管有晚唐墓葬的例子存在,但常盘山壶、私人藏壶的紧绷感使它很难被定为唐代。底足的支钉也不符合唐代的做法。该壶大量丰满的贴花装饰的印象与唐代的不同。

因此,通过与已知的现存例子进行比较,并考虑到目前对这些时期器物的理解,将常盘山壶的年代定为隋朝似乎更为合适,而私人藏的文壶应该是北齐的作品。

龙泉堂的文壶釉色偏薄,造型、做法与河北易县、蔚县出土的作品类似,虽然标注隋-唐,但应该定为唐代的作品。

On the other hand, despite the existence of examples from late Tang tombs, the tension and aura of the Tokiwayama Jar and private collections makes it difficult to assign them to the Tang dynasty. The spikes on the foot are also not consistent with Tang dynasty practice. The impression of the pot's extensive and voluminous appliquéd decoration is different from that of the Tang dynasty.

Therefore, by comparing it with known extant examples and taking into account the current understanding of wares from these periods, it seems more appropriate to date the Tokiwayama Bunko to the Sui dynasty, whereas the Jar in the private collection would have been from the Northern Qi.

The Jar from the Mayuyama Ryusendo has a thin glaze and is similar in form and practice to pieces excavated in Yixian and Weixian counties in Hebei, and although labelled Sui-Tang, it should be dated to the Tang dynasty.

Comments