漢代筆記 vol.5 何鴻卿爵士3500萬港元的青銅辟邪 - Sir Joseph Hotung’s 35 million HKD bronze Bixie.

- SACA

- Aug 12, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Nov 5, 2024

一隻何鴻卿(Sir Joseph Hotung)的辟邪,被定為漢代,2022年10月拍得3546.5萬港幣,由著名古董商Daniel Eskenazi投得。

這件作品一直被放在何鴻卿爵士的書桌上,中國古代當官靠的是科舉,是一套非常嚴謹的制度。書桌案頭便是與帝王相處之余的精神世界,以蘇軾為代表的文人,一直以來都有案頭賞玩的藝術品作為精神寄託,這套傳統被一直傳遞下來。這種傳統,甚至影響了帝王,比如乾隆皇帝。

何鴻卿爵士的案頭,便是一個中國傳統文人十分真實的寫照。

A Sir Joseph Hotung bronze 'bixie', attributed to the Han Dynasty, fetched HK$35,465,000 in October 2022, won by Daniel Eskenazi, a renowned antique dealer from London, UK.

The piece had been sitting on Sir Joseph's desk. In ancient China, officialdom was based on the imperial examinations, a very rigorous system. The desk was the spiritual world of the emperor, and the literati, represented by Su Shi, have always had artworks on their desks as their spiritual support, a tradition that has been passed on ever since. This tradition also influenced the emperors, such as the Qianlong Emperor.

The desk of Sir Joseph is a very realistic portrayal of a traditional Chinese literati.

An important and outstanding bronze male chimera, bixie, Han dynasty | 漢 青銅辟邪

Han dynasty

漢 青銅辟邪

cast in a powerful striding stance, the right front leg stretched forward and the left hind leg extended, the thick paws slightly lifted off the ground exposing sharp claws, its head raised alertly and dominated by piercing eyes and furrowed brows, the ferocious horned beast portrayed with gaping jaws above a tuff of beard, the broad muscular body accentuated with elaborate scrollwork against a ground of swirls and hatching, flanked by feathery wings detailed with striations and terminating in a sinuous tail with feathery protrusions and tufts of fur, the back surmounted by a rectangular and a circular socket incised with concentric circles and triangles, the underside cast with male genitals

l. 27 cm, h. 18 cm

In overall excellent condition except for an old loss to the tip of its tail. Typical minor casting flaws original to manufacture, including a small hole to the back of its head and original patches below the body (one patch visible in the catalogue image). The surface with age-related wear and expected minor dents typical for archaic bronzes. X-rays are available upon request.

整體品相良好,唯尾巴末端見一舊傷。常見青銅器鑄造瑕疵,包括頭後一小鑄孔,後腿及腹部有鑄造老補(其中後腿處老補在圖錄圖片中可見)。器物表面見青銅器常見小磕碰及磨損。

Provenance

L. Wannieck, Paris, 1924 or earlier.

Collection of Baron Adolphe Stoclet (1871-1949), Brussels, 1934 or earlier.

Collection of Madame Raymonde Féron-Stoclet (1897-1963), Brussels, and thence by descent.

Eskenazi Ltd, London, 25th March 2003.

L. Wannieck,巴黎,1924年或以前

阿道夫.斯托克萊特男爵(1871-1949年)收藏,布魯塞爾,1934年或以前

Raymonde Féron-Stoclet 夫人(1897-1963年)收藏,布魯塞爾,此後家族傳承

埃斯卡納齊,倫敦,2003年3月25日

Literature

Michael Rostovtzeff, 'L'Art Chinoise de l'Epoque de Han', Revue des Arts Asiatiques, vol. 1, no. 3, Paris, October 1924, p. 11.

Georges Salles, Bronzes Chinois des Dynasties Tcheou, Ts'in and Han, Paris, 1934, cat. no. 417.

Osvald Sirén, 'Indian and Other Influences in Chinese Sculpture', Studies in Chinese Art and Some Indian Influences, London, 1938, pp. 15-36, pl. III, fig. 16.

Osvald Sirén, Kinas Konst under Tre Artusenden, vol. I: FranForhistorisk Ted Till Tiden Omkring 660 e. Kr., Stockholm, 1942, p. 272, fig. 190.

H.F.E. Visser, Asiatic Art in Private Collections of Holland and Belgium, Amsterdam, 1948, pl. 61, no. 148a.

Georges A. Salles and Daisy Lion-Goldschmidt, Collection Adolphe Stoclet, Brussels, 1956, pp. 390-91.

Chinese Works of Art from the Stoclet Collection, Eskenazi Ltd, New York, 2003, cat. no. 10 and back cover.

Giuseppe Eskenazi in collaboration with Hajni Elias, A Dealer’s Hand. The Chinese Art World Through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi, London, 2012; Chinese version, Shanghai, 2015, reprint, 2017, fig. 28.

Michael Rostovtzeff,〈L'Art Chinoise de l'Epoque de Han〉,《Revue des Arts Asiatiques》,卷1,第3期,巴黎,1924年10月,頁11

Georges Salles,《Bronzes Chinois des Dynasties Tcheou, Ts'in and Han》,巴黎,1934年,編號417

喜龍仁,〈Indian and Other Influences in Chinese Sculpture〉,《Studies in Chinese Art and Some Indian Influences》,倫敦,1938年,頁15-36,圖版3,圖16

喜龍仁,《Kinas Konst under Tre Artusenden》,卷I:Fran Forhistorisk Ted Till Tiden Omkring 660 e. Kr.,斯德哥爾摩,1942年,頁272,圖190

H.F.E. Visser,《Asiatic Art in Private Collections of Holland and Belgium》,阿姆斯特丹,1948年,圖版61,編號148a

Georges A. Salles 及 Daisy Lion-Goldschmidt,《Collection Adolphe Stoclet》,布魯塞爾,1956年,頁390-91

《Chinese Works of Art from the Stoclet Collection》,埃斯卡納齊,紐約,2003年,編號10及封底

埃斯卡納齊,薛好佩整理,《中國藝術品經眼錄:埃斯卡納齊的回憶》,倫敦,2012年,中譯版,上海,2015年,2017年再版,圖28

Virility to Avert Evil Spirits

Regina Krahl

This bronze animal, although not monumental in size, has a universal sculptural quality that carries it well beyond the confines of Chinese art. With its imaginative, fanciful physique and dynamic quasi-naturalistic bearing, it can hold a place in any history of world art. The basic image of a mighty but not ferocious animal, depicted in a state of utmost alertness that makes one expect an immediate jump or other rapid movement, expresses qualities valued in any animal sculpture and achieved rarely as strikingly as in this figure.

The Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) is the last period that can still be counted to the Bronze Age, but as bronze was no longer the one material vital for daily life and for ritual, it was increasingly explored also as an artistic medium. When looking at this dramatic sculpture, there can be no doubt that bronze casting had come a long way since its beginnings in the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – 1045 BC), when animals tended to be shown in a distant, awe-inspiring mode. In the late Warring States period (475 – 221 BC) began an interest in animal sculptures rendered in naturalistic poses and movements. This perceived naturalism made mythical creatures, cherished as guardians and benevolent supporters of men, seemingly more approachable.

Fabulous animals springing from an artist’s imagination exist throughout the world. Related winged and horned mythical creatures were depicted already earlier in regions to the west of China and appear, for example, in Achaemenid glazed brickwork from palaces of King Darius (r. 522-486 BC) in Susa, Iran, and are also seen on precious metalwork. In the West, they are usually called chimeras, although the original Greek chimera, also a creature combining features of several animals, was a fictional female monster. In China, several terms were in use at the time for such fanciful beasts, such as tianlu, bixie, or qilin (Ann Paludan, The Chinese Spirit Road. The Classical Tradition of Stone Tomb Statuary, New Haven and London, 1991, p. 42), but the present feline animal with horns, wings and claws is generally known as bixie, which signifies ‘to avert evil spirits’.

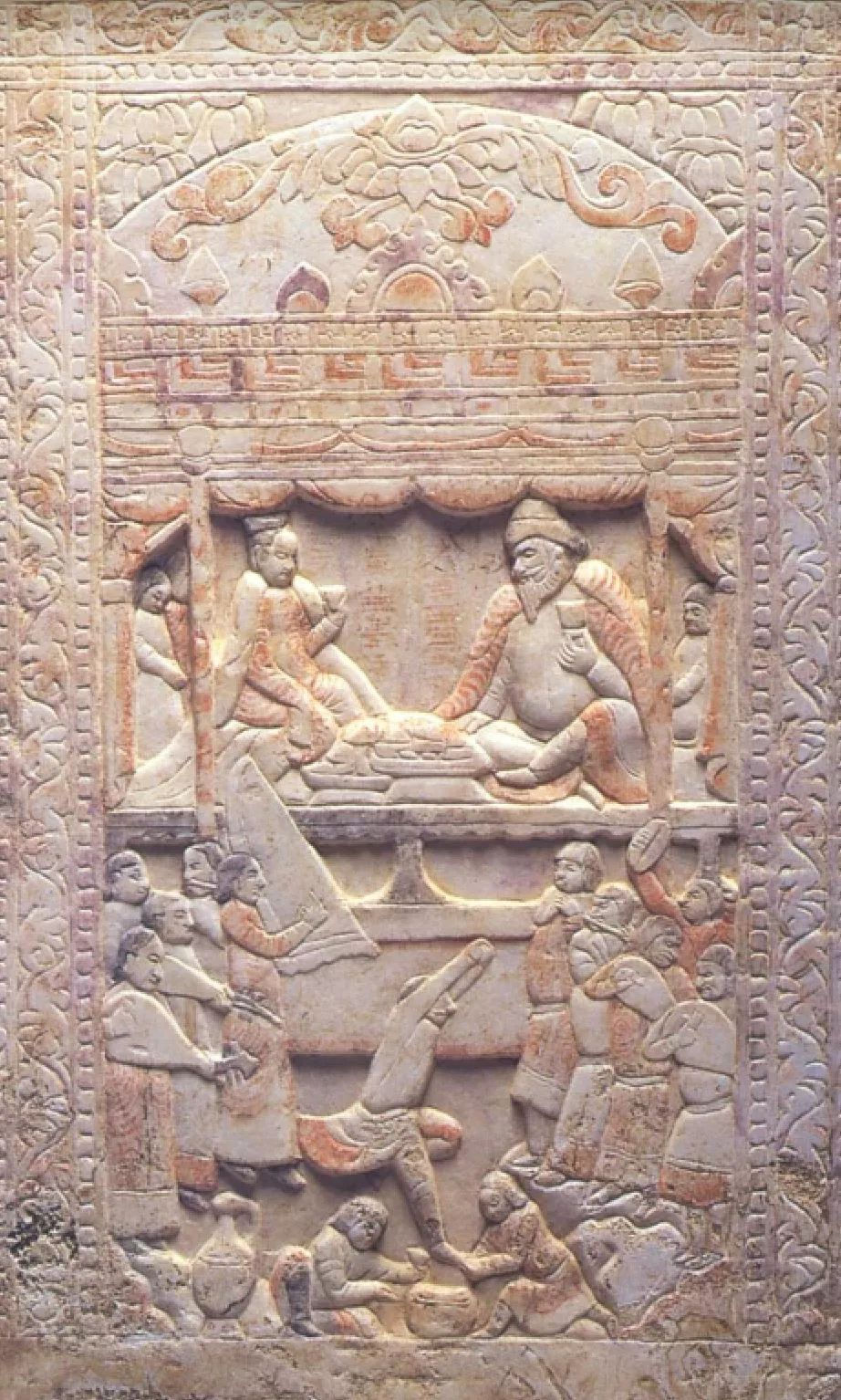

FIG. 1 A BRONZE FITTING IN THE FORM OF A SUPERNATURAL ANIMAL, EASTERN HAN DYNASTY © FREER GALLERY OF ART, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, WASHINGTON, D.C.: PURCHASE — CHARLES LANG FREER ENDOWMENT, F1961.3

圖一 東漢 青銅異獸構件 © 華盛頓史密森學會佛利爾美術館 以查爾斯.朗.弗利爾捐贈基金購藏 F1961.3

In the Han dynasty, such inspiration from abroad would have fallen on fertile ground. Many books of a Daoist nature were circulating, fostering belief in the power of super-natural beings, and the mythological work Shanhaijing(Classic of Mountains and Lakes), probably compiled over a lengthy period prior to and throughout the Han dynasty, described them directly. “The book poses as a guide to travellers visiting holy mountains and other sites within China, informing them of the strange creatures, animal, hybrid, and spiritual, that they may encounter in their wanderings; of the powers that such creatures may wield; and of the consequences of meeting them, consuming their flesh, or wearing their fur” (Loewe in Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe, The Cambridge History of China, vol. 1: The Ch’in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge, 1986, p. 658). Compared to the fanciful creatures described in the Shanhaijing, this chimera, however, seems like a tame version, not that far removed from a real animal.

The visual culture of the period was accordingly also full of mythical beings and demonic figures, inhabiting imaginary realms together with real animals and birds, as for example, depicted on the black-lacquered coffin of Lady Dai, who was buried around 168 BC at Mawangdui near Changsha, Hunan (see Changsha Mawangdui yi hao Han mu/The Han Tomb No.1 at Mawangtui, Changsha, Beijing, 1973, vol. 2, pls 27-31, 38-57). While fabulous animals were frequently depicted in two-dimensional form, sculptures, worked in the round, are rare in the Han. Bronze animals that exist from this time mostly had a practical purpose, being cast as fittings, weights, tallies, belt hooks or supports carrying lamps, incense burners, frames for musical instruments and other items of perishable material which have not survived. Such bronzes were most probably used in daily life, even if some were eventually buried with important personalities.

As a Han bronze animal sculpture, the present chimera is already rare, but the way it is represented is particularly unusual. Its creator – in this case the artist who created the clay model for the casting – clearly aimed to express unbridled masculine vitality which, by association, would render the same to the patron who commissioned it and to any eventual owner, who could identify with it. It depicts an animal at the height of its physical strength. The highly unusual detail of clearly rendered male genitals would probably have remained unseen and were probably never meant to be seen, since this figure was not made for handling and once it was fitted as a support, this would have been impossible in any case. Clearly, this naturalistic feature was the artist’s means of imbuing his bronze with life, of encapsulating in it the virility that would empower the animal with the spiritual energy required to avert evil.

A very similar chimera-shaped fitting, but not its pair, is in the collection of the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (F 1961.3), bought by Charles Lang Freer from J.T. Tai, New York (fig. 1). It shows the same animal in the same pose, but with longer peacock feathers at its wings and tufts of hair at its legs, and with an opening at the back, where it may have had similar sockets. One other similar bronze figure is known, also with sockets at its back, formerly in the collection of Mrs Grace Rogers and included in the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935-36, cat. no. 500, where it is attributed to the Six Dynasties period (220-589).

The sculptors of these figures have shown the animal in a state of breathless attention, conveying tension of body and mind with muscles and sinews flexed and eyes focussed. Immediately reminiscent in general concept, but capturing nowhere near the bodily energy of the present piece are the monumental stone sculptures of bixie that were placed as tomb guardians on spirit ways in front of important tombs. These massive animals (typically 2.75 m tall, 3 m long) are depicted in the same way as the bronze figures, walking in this other-worldly manner, with only the pads of their feet touching the ground, their toes raised and kept free of the dust of the earth, but their pose tends to be rather static or at best resembling a leisurely walk.

FIG. 2 A STONE WINGED CHIMERA, EASTERN HAN DYNASTY, FOUND IN MENGJIN, HENAN, IN 1992; LUOYANG MUSEUM, HENAN

圖二 東漢 石雕辟邪 1992年河南孟津縣出土 河南洛陽博物館

Stone winged animals, but without horns, from an Eastern Han tomb near Luoyang, now in the Luoyang Museum of Ancient Arts at Guanlin Temple, are illustrated in Paludan, op. cit., pl. 36, and in Zhongguo meishu quanji: Diaosu bian [Complete series on Chinese art: Sculpture section], Beijing, 1988, vol. 2, pl. 93; another, perhaps from the tomb of Emperor Guangwu (r. 25-57), is illustrated in James C.Y. Watt et al., China. Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2004, no. 1 (fig. 2). Victor Segalen encountered similar figures in Sichuan (The Great Statuary of China, posthumously published, Chicago, 1978, pls 2 and 3 and fig. F). Several slightly later stone figures of this type are still guarding tombs in the region of Nanjing, capital of the Chinese-ruled south after the Han dynasty; see, for example, one in front of the imperial tomb of Song Wendi (r. 424-53), illustrated in Paludan, op.cit., pl. 59 and in Watt et al., op.cit., p. 25, fig. 22.

Chimeras carved in jade are also known from the Han period, but are generally rendered in a reclining pose that required less material; one jade bixie of very similar overall form and pose, however, with a single circular socket on its back, was excavated from a Han tomb in a northern suburb of Baoji in Shaanxi, included in the exhibition Tan Shengguang, ed., Yu tian jiu chang. Zhou Qin Han Tang wenhua yu yishu/Everlasting like the Heavens. The Cultures and Arts of the Zhou, Qin, Han, and Tang, Shanghai, 2019, pp. 372-3 (fig. 3).

A very similar horned and winged fabulous creature, but very differently depicted, crouching low to the ground, can also be seen in an exquisite bejewelled gilt-bronze ink-stone box excavated from an Eastern Han tomb of the 2nd/3rd century at Xuzhou, Jiangsu, and now in the Nanjing Museum, see Watt et al., op.cit., no. 5. In the Six Dynasties period, bixie were also depicted in various other media, particularly in China’s southern regions, for example, in green-glazed stoneware, but generally in a much less lively fashion than the present figure.

FIG. 3 A JADE WINGED CHIMERA, HAN DYNASTY, EXCAVATED FROM BAOJI IN 1978 © BAOJI BRONZE WARE MUSEUM, BAOJI, SHAANXI

圖三 漢 玉辟邪 1978年寶雞出土 ©陝西寶雞青銅器博物院

We do not know what this animal would have supported, but similar circular and rectangular sockets are held by a kneeling winged divine figure cast in bronze, discovered in an Eastern Han tomb at the outskirts of Luoyang, Henan province; see Stephen Little with Shawn Eichman, Taoism and the Arts of China, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, 2000, no. 21 (fig. 4). Animals such as the present piece are by some scholars believed to have served as screen supports.

The figure, which is recorded since 1924, formed part of the renowned collection of Adolphe Stoclet and is reminiscent of another bronze animal, perhaps the most famous piece from the Stoclet collection, a large bronze winged dragon figure (fig. 5). This magnificent animal, now one of the highlights in the collection of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, where it holds pride of place, is slightly earlier in date, attributed to the Warring States period, but is depicted in a similarly powerful pose, with similar feathery wings and raised toes, a similar scroll pattern marking its skin, and also represents a fitting. It has been illustrated many times, for example, in Thomas Lawton, ‘The Stoclets: Their Milieu and Their Collection’, Orientations, vol. 44, no. 1 (January/February 2013), p. 71, fig. 5, and was included in the Royal Academy of Arts exhibition, London, 1935-36, no. 489.

Baron Adolphe Stoclet (1871-1949), a Belgian banker and industrialist, and his wife Suzanne were highly enterprising art collectors and patrons. The two bronze animals formed part of the vast collection of important works of art from all over the world, on display in Palais Stoclet (fig. 6), an Art Deco work of art in itself, that is still preserved in Brussels. This mansion and its garden had been conceived for the Stoclets down to the last detail by the important Austrian architect and designer Josef Hoffman (1850-1956) and are considered his main surviving oeuvre. Many artists of the influential modernist workshops Wiener Werkstätten contributed to this ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (total work of art), foremost among them the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), who decorated the dining room with a mosaic frieze. A view of the interior of Palais Stoclet with a glass vitrine containing Chinese antiquities is published in Lawton, op. cit., p. 68, fig. 2.

辟邪護生

康蕊君

青銅辟邪,尺寸非鉅,雕塑氣勢萬千,超越中國藝術傳統範疇,造形融合想像、自然,姿態生動有力,如此成就應屬世界藝術史之重要一頁。發想原型為尊貴獸王,高度警覺之瞬,張牙振翅,下一秒即欲前撲,以靜態雕塑捕捉如此千鈞一髮時刻,難能可貴,珍稀非凡。

漢朝屬青銅時代之末,雖逐漸少以青銅為單一材質,製作日常使用、祭祀禮器等,其鑄造技術之臻熟,更促使發展青銅器藝術表現。觀此可見,青銅藝術發展的悠久歷史,商朝時,青銅工藝描寫萬獸,常以出世脫俗、使人敬仰之貌呈現,戰國時代晚期,動物描寫的姿態,逐漸更加貼近自然,如此變化使得傳說中守護生靈、庇佑世人的神獸形象,愈見靈動如真,親切可人。

源自想像之神獸,世界各文化皆有,相類的帶翅、角之獸,可見於古伊朗舒什地區,阿契美尼德王朝大流士一世國王的宮殿釉磚,及珍貴金屬器上。在西方,多稱之為凱美拉,此詞源自希臘,原文意指多種生物特徵混合之神話母獸。在中國,相類神獸名稱甚多,如天祿、辟邪、麒麟(Ann Paludan,《The Chinese Spirit Road. The Classical Tradition of Stone Tomb Statuary》,紐黑文及倫敦,1991年,頁42),此像帶角、翅、爪,多稱為辟邪,意謂趨避邪靈。

FIG. 4 A GOLD-INLAID BRONZE KNEELING WINGED FIGURE WITH SOCKETS, EASTERN HAN DYNASTY, 2ND CENTURY, EXCAVATED FROM THE OUTSKIRTS OF LUOYANG IN 1987; LUOYANG MUSEUM, HENAN

圖四 東漢二世紀 鎏金銅羽人 1987年洛陽市郊出土 河南洛陽博物館

漢朝各類神仙思想盛行,民間流傳大量道家典籍,各種生靈信仰遍地開花,《山海經》收錄多數漢朝及更早之民間信仰,「此書可做為悠遊中國諸座靈山、靈地的導引,記載各地傳說之奇特生物、靈獸、神獸及靈體,他們各自的獨特能力,及可能之後果,如生吞剝皮等」(Denis Twitchett 及 Michael Loewe,《The Cambridge History of China, vol. 1: The Ch’in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge》,1986年,頁658)。比較《山海經》中所述奇獸,此尊辟邪似較溫和,更接近於真實動物。

相應地,漢朝圖像文化亦飽藏各式神仙、妖物,與真實世界的生物、鳥類混居一處,如湖南長沙馬王堆出土辛追夫人黑漆棺上之裝飾,見《長沙馬王堆一號漢墓》,北京,1973年,卷2,圖版27-31、38-57。如此圖像多見於漢朝平面繪畫,雕塑類立體作品甚稀,銅作多為日常器物,如飾件、鎮紙、符、帶鉤、燈足、香爐、樂器飾框,其他有機材質所製物品,多已隨年月腐化佚失。這類器物為日常用品,墓葬時少數會跟隨身份重要的墓主入土。

本品身為漢代動物銅雕,已是罕得,其題材更是難得一見。製作青銅辟邪,匠人需先塑土模,力求彰顯辟邪雄姿英風,此英氣呼應其主人之特質,神采煥發,正處於精力之巔,特別塑其雄性性徵,非醒目之處,因本品非把件,應為器足,用以支撐物件,一般觀者應難以一見。然如此細膩描寫,為本像更加注入生氣,神威勃發,足以抵禦任何外邪。

華盛頓弗利爾美術館典藏一件青銅辟邪,與本品甚是相近,但非成對,乃查爾斯.朗.弗利爾購自紐約戴潤齋(圖一),同為辟邪且姿態一致,但羽翼上的孔雀翎羽、腿後側毛更長,背上有孔,原或亦有相類的管座。另一件相類作例,背上同有管座,曾為 Grace Rogers 夫人珍藏,見《參加倫敦中國藝術國際展覽會出品圖說》,英國皇家藝術學院,倫敦,1935-36年,編號500,當時斷為六朝。

此批青銅辟邪神態令人屏息,目光專注,肌腱緊繃,炯炯有神,張力十足,遙遙呼應漢墓神道二側,用以守護墓主的巨型石雕辟邪,約2.75公尺高,3公尺長,氣勢尊貴非凡,僅足掌輕觸地面,足趾高昂,不染塵埃,姿態靜止,彷彿至多為優閒漫步。

FIG. 5 A BRONZE WINGED DRAGON, EASTERN ZHOU DYNASTY, WARRING STATES PERIOD, FORMERLY IN THE COLLECTION OF ADOLPHE STOCLET; LOUVRE ABU DHABI

圖五 東周戰國時期 青銅翼龍 阿道夫.斯托克萊特舊藏 阿布扎比羅浮宮

LAD 2017.001 © DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE AND TOURISM – ABU DHABI / PHOTO MOHAMED SOMJI - SEEING THING MOHAMED SOMJI - SEEING THINGS/© DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE AND TOU

洛陽古代藝術博物館藏一件石雕帶翅神獸,無角,出自洛陽市郊東漢墓,刊於 Paludan,前述出處,圖版36,及《中國美術全集:雕塑編》,北京,1988年,卷2,圖版93;另一例,或原出自漢光武帝墓,出版於屈志仁等,《China. Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD》,大都會藝術博物館,紐約,2004年,編號1(圖二)。Victor Segalen 也曾在四川見過類似雕塑,《The Great Statuary of China》,芝加哥,1978年,圖版2、3,圖F。漢朝之後,東晉、南朝定都南京,此處部分墓葬仍見大型石雕,如宋文帝墓 ,錄於 Paludan,前述出處,圖版59,及屈志仁等,前述出處,頁25,圖22。

漢代玉雕辟邪,多為趴伏姿態,以撙節用材。陝西寶雞北郊漢墓出土一件玉雕辟邪,造形、姿態與本品相似,背上帶圓形孔插,展出於談晟廣編,《與天久長:周秦漢唐文化與藝術》,上海,2019年,頁372-3(圖三)。

江蘇徐州約二至三世紀東漢墓出土一件嵌寶鎏金硯盒,採辟邪之形,瑞獸帶翅蹲踞,現貯南京博物院,見屈志仁等,前述出處,編號5。六朝時,辟邪形象可見於不同材質器物,如綠釉陶瓷,但罕有如本品生氣蓬勃者。

本品原為何類器物之座足,已無從知悉,但可參考河南洛陽郊外東漢墓出土一青銅跪姿羽人,雙手扶著類同類似本品之圓形與方形管孔,見 Stephen Little 與 Shawn Eichman,《Taoism and the Arts of China》,芝加哥藝術學院,2000年,編號21(圖四)。有學者認為,如本品此類動物造像,或應為屏風底座。

此青銅辟邪之流傳史,可溯自1924年,時為著名的阿道夫.斯托克萊特珍藏,呼應另一件斯托克萊特的知名藏品,大型青銅翼龍像(圖五),青銅翼龍現為阿布扎比羅浮宮鎮館珍寶,年代更早,屬戰國時代之作,叱吒軒昂,姿態張力十足,與本品相類,羽翼豐美,足趾高揚,身軀飾類同卷龍紋,也是器物飾件,曾多次出版,如 Thomas Lawton,〈The Stoclets: Their Milieu and Their Collection〉,《Orientations》,卷44,編號1(2013年1月至2月),頁71,圖5,見前述英國皇家藝術學院中國藝術國際展覽會,倫敦,1935-36年,編號489。

FIG. 6 PALAIS STOCLET, BRUSSELS, BELGIUM, BUILT BY AUSTRIAN ARCHITECT JOSEF HOFFMANN IN 1905-11

圖六 比利時布魯塞爾斯托克萊特宮 奧地利建築師約瑟夫.霍夫曼建於1905-11年

阿道夫.斯托克萊特男爵(1871-1949年)為比利時銀行家與企業家,與夫人 Suzanne 皆為藝術贊助人與收藏家,青銅辟邪與翼龍為他們廣大藝術收藏之一角,其全貌涵蓋許多世界重要藝術作品,皆藏於布魯塞爾的斯托克萊特宮(圖六),建築本身亦是裝飾藝術之珍寶。此大宅與花園為知名奧地利建築師約瑟夫.霍夫曼(1850-1956年)專為斯托克萊特家族打造,亦被視為其代表作。建築設計結合許多重要現代藝術家之作品,悉心特製,以成就所謂「總體藝術作品」,其中最富盛名要屬奧地利畫家古斯塔夫 · 克林姆(1862-1918年),為餐廳設計大型馬賽克壁畫。一禎紀錄斯托克萊特宮內,展示中國古物收藏玻璃櫃的照片,錄於Lawton,前述出處,頁68,圖2。

Comments