宋代筆記 Vol.97 坂本五郎:408万成交南宋青白釉劃童子花卉紋梅瓶 - Sakamoto Goro, A Extremely Rare Qingbai 'Boys' Meiping, Southern Song Dynasty.

- SACA

- Oct 10, 2024

- 17 min read

Updated: Oct 29, 2024

408万成交

90万书面,100万carrie,140万场内女士,150万carrie,180万,190万carrie好像志在必得,240sonya,260线上,300sonya,320万电话,基本上现场退出?这件还是非常难得的作品。320万,坂本五郎都要哭了。340万落槌,14号牌

這件梅瓶曾經在2014年蘇富比紐約的坂本五郎專場以 2,500,000 — 3,000,000 USD上拍,在當時是一個非常高的價格,但隨著這些年青白磁梅瓶水漲船高,這個價格不再是不合理了。儘管如此,這次蘇富比將以HK$ 300,000-600,000(US$ 38,500-77,000)上拍,相信會有很激烈的爭奪。

This vase was previously offered at Sotheby's New York sale in 2014 for 2,500,000 - 3,000,000 USD, a very high price, but with the rise of blue and white magnetic vases over the years, this price is no longer unreasonable. Nonetheless, Sotheby's will offer this bottle at HK$300,000-600,000 (US$38,500-77,000), which is sure to be hotly contested.

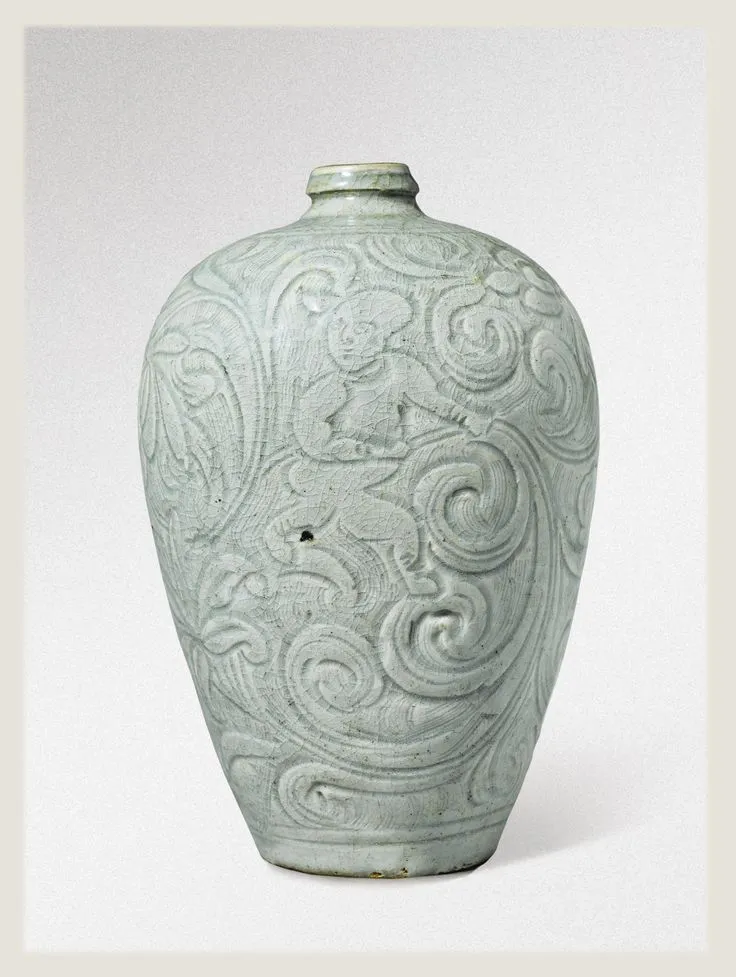

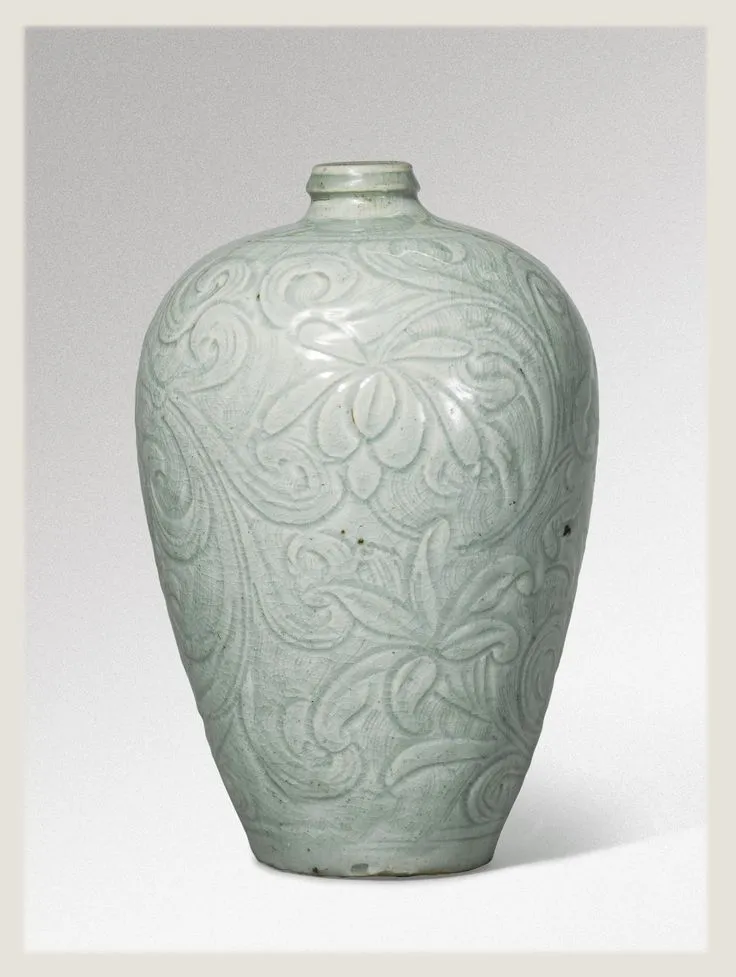

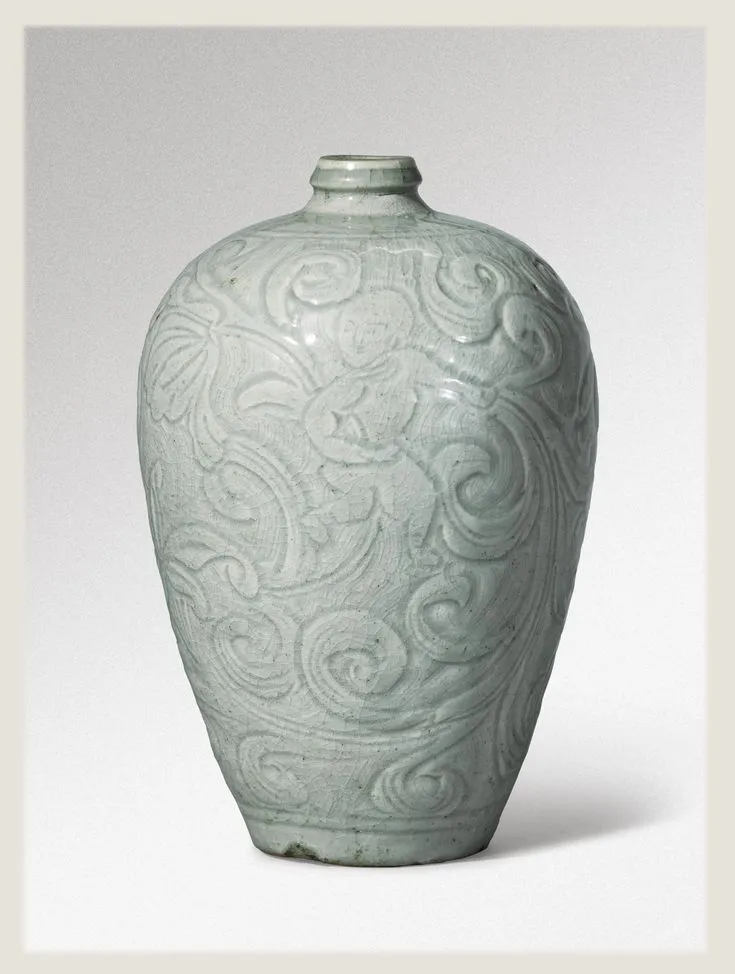

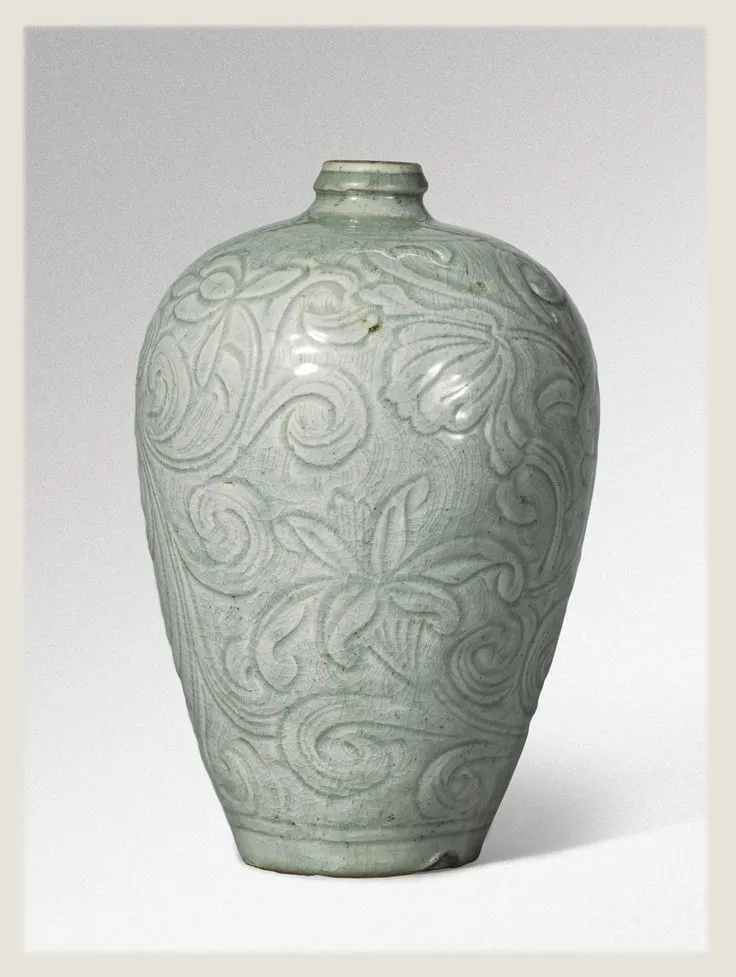

梅瓶滿刻卷草童子紋,靈動活潑。青白瓷飾以此紋者一般以碗盤等較小器物為多,器大如此例者稀。本器底紋劃花疏密有致,變化豐富,刻劃童子更顯立體生動,仿如浮雕。

此例以手刻花紋飾大器,遒勁俐落,青白瓷有薄巧細密者,亦有較厚重堅緻者如此瓶。青白瓷非以其產地得名, 而是因其青白相映、瑩潤恬靜的色澤著稱,胎質細膩潔白,又稱為「影青」、「映青」,出於贛閩皖三省,南宋蔣祈所著《陶記》中描述江西景德鎮所製佳瓷如美玉,「景德陶昔三百餘座。埏埴之器,潔白不疵,故鬻於他所,皆有饒玉之稱」。青白瓷後經改良可能成為青花瓷之濫觴,早期景德鎮陶匠或以越窰為發端,時至五代北宋, 則轉取法定窰之美,本器劃花飽滿流暢,或可為證。

一件相近梅瓶作例,刻纏枝蓮花童子紋圖,應出土自京都法勝寺遺跡,現藏於日本京都國立博物館,圖錄於長谷部樂爾等編,《世界陶磁全集》,卷12,宋,東京,1977 年,彩色圖版270,以及長谷部樂爾及今井敦, 《中國之陶磁》,卷12:日本出土之中國陶磁,東京,1995年,彩色圖版57。比較另一瓶例,同刻童子紋,唯卷草紋更為細密,藏於濱松市美術館,並曾展於《宋磁》,東武美術館, 東京,1999年,編號50;另有一連蓋瓶例, 飾較小童子紋飾,芝加哥美術館藏,圖見《歐美蒐藏中国陶磁図録》,東京,1960年,圖版54,後再圖錄於《海內外徐展堂中國藝術館藏品選萃》,1996年,圖版100。此外尚可參照一瓶例,刻嬰戲牡丹紋葉,出自玫茵堂典藏,圖錄於康蕊君,《玫茵堂中國陶瓷》,卷1,倫敦,1994年,圖版608。另一相近瓶例,器形略大,售於紐約佳士得1999年3月22日,編號258。

三兩小兒攀爬於花叢之紋飾,流行自唐代晚期以降,多見於銀、銅、織品、玉器及瓷器。據Jan Wirgin述,其源應詮釋重組自印度洞窟壁畫,以及唐代佛教紋飾主題,以嬰孩坐蓮代表靈魂輪迴重生,見《Sung Ceramic Designs》, 哥德堡,1970年,頁179-184。作者論述,嬰孩花卉紋飾之流行,主要源於其多子多福之美好寓意(頁181)。

此卷草童子紋青白盌,參考出自羅啟妍典藏作例, 曾展於《如銀似雪》,丹佛美術館,丹佛,1998年, 編號39;另一近例,錄於《世界陶磁全集》,卷12, 東京,1977年,圖版162及163。亦可參考青白梅瓶數例,刻類近卷草花卉紋飾,其一為芝加哥美術館館藏,出處同上,圖版167;其二為四川省博物館館藏,見《中國陶瓷全集》,卷8,宋(下),1999年,圖版179。

the ovoid body rising to a broad round shoulder and short narrow waisted neck with carinated mouth, boldly decorated around the exterior on either side with a pair of freely incised figures of boisterous young boys, interrupted by a luxuriant floral meander of lily and lotus blooms all borne on scrolling stems, all within double-line bands, covered overall in a rich ice-blue glaze pooling to darker tones within the carved recesses and falling short of the unglazed foot revealing the off- white body, Japanese double wood boxes

28.6 cm

HK$ 300,000-600,000

US$ 38,500-77,000

展覽

《中国名陶百選展》,髙島屋,東京・1960年, 編號40

《中國宋元美術展》,東京國立博物館, 東京,1961年,編號241

《中国名陶百選展》,髙島屋,大阪,1961年, 編號43

《東京オリンピック記念 古美術名品図録》, 不言堂,東京,1964年,编號58

《新館完成記念特別展覧会図版目録》,京都国立 博物館,1966年,編號269

《中国陶磁展》,秋田市美術館,1966年,編號8

出版

林屋晴三,《中國之陶磁》,1955年,編號3 小山富士夫編,《中國名陶百選》,東京,1960 年,頁63

長谷部楽爾,《世界陶磁全集》,卷十二:宋,東京,1977年,編號166

Exhibited

Chugoku Meito Hyaku-sen/A Loan Exhibitionof One Hundred Selected Masterpieces from Collections in Japan, England, France and America, Takashimaya, Tokyo, 1960, cat. no. 40.Chugoku So Gen Bijutsu ten/Chinese Arts of the Sung and Yuan Periods, Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, 1961, cat. no. 241.Chugoku Meito Hyaku-sen /A Loan Exhibitionof One Hundred Selected Masterpieces, Takashimaya, Osaka, 1961, cat. no. 43.Tokyo Olympic Kinen Kobijutsu Meihin zuroku [Tokyo Olympic Memorial Masterpieces of antiquities], Fugendo, Tokyo, 1964, cat. no. 58. Shinkan kansei kinen tokubetsu tenrankai zuhan mokuroku/Illustrated Catalogues of the Special Exhibition in Memory of the New Building, Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto, 1966, cat. no. 269. Chugoku toji ten [Exhibition of Chinese ceramics], Akita Municipal Museum of Art, Akita, 1969, no. 8.

Literature

Seizo Hayashiya, Chugoku no Touji [China's Ceramics], Tokyo, 1955, cat. no. 3.Fujio Koyama ed., Chinese Ceramics: One hundred selected masterpieces from collections in Japan, England, France and America, Tokyo, 1960, p. 63.

Gakuji Hasebe, Ceramic Art of the World - Volume 12 - Sung Dynasty. Tokyo, 1977, cat. no. 166.

Outstanding for the deftly carved design of large figures of boys playing amongst scrolling vines, it is rare to find qingbai vases decorated with this scene which more commonly adorned smaller surfaces such as bowls and dishes. The combed lines of the background add structure and variation to the design, allowing the figures to stand out as if in relief.

The present vase distinguishes itself with its robust and confidently carved decoration. Qingbai wares ranged from thin and delicate to more stoutly potted forms such as the present example. Produced at a number of kilns in the provinces of Jiangxi, Fujian and Anhui, qingbai ware, also known as yingqing, refers not to the locales where the kilns were located but to their appearance. Qing (green) and bai (white) denote the alluring pale blue-green tones of the brilliant translucent glaze which so effectively complimented the white porcelaneous body beneath. The Southern Song ceramic historian Jiang Qi notes in his treatise Tao ji (Ceramic Records) that white porcelain produced in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province was so refined and pure that it was known as raoyu (Jade of Rao), the region in which the Jingdezhen kilns were located. With some kiln modification, it is probable that these wares served as the foundation for the blue-and-white porcelain tradition of China from the 14th century onward. Although the early potters at Jingdezhen may have modelled their earliest qingbai pieces on Yue ware, by the Five Dynasties and Northern Song periods they often looked to Ding ware for aesthetic inspiration. This inspiration is perhaps evident on the present vase with its swift, confident lines of carving.

A similar meiping carved with large boys among lotus scrolls on a combed ground, probably excavated from the ruinsof the Hosshō-ji, Kyoto, and now in the Kyoto National Museum, is illustrated in Hasebe Gakuji, ed., Sekai tōji zenshū/Ceramic Art of the World, vol. 12: Sō/Sung Dynasty, Tokyo, 1977, col. pl. 270, and in Hasebe Gakuji and Imai Atsushi, Chūgoku no tōji/Chinese Ceramics, vol. 12: Nihon shutsudo no Chūgoku tōji/Chinese Ceramics Excavated in Japan, Tokyo, 1995, col. pl. 57. Compare also a vase of this type, but carved with boys amongst a denser scrolling vines, from the Hamamatsu Municipal Museum of Art, Hamamatsu, included in the exhibition Song Ceramics, Tobu Museum of Art, Tokyo, 1999, cat. no. 50; and another with cover, decorated with smaller figures of boys, in the Art Institute of Chicago, illustrated in Chinese Ceramics in the West, Tokyo, 1960, pl. 54, and again in Splendour of Chinese Art. Selections from the Collections of T.T. Tsui Galleries of Chinese Art Worldwide, Hong Kong, 1996, pl. 100. See also a baluster vase with a flared foliate mouth, also carved with boys playing among scrolling peonies and camellias, all against a similar combed ground, in the Meiyintang collection, illustrated in Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, vol. 1, London, 1994, pl. 608. A closely related vase, of slightly larger size, was offered at Christie’s New York, 22nd March 1999, lot 258.

Designs depicting two or three small boys climbing stems of flowers were popular on a variety of objects and media including silver, bronze, textile, jade and various types of ceramics from the late Tang dynasty onwards. Jan Wirgin, in Sung Ceramic Designs, Goteborg, 1970, pp 179-184, discusses the origin of the design, suggesting it is an amalgamation and reinterpretation of Indian cave paintings of boys and the Buddhist motif of children representing reborn souls seated on lotus flowers from the Tang dynasty. Wirgin states that the main cause for the marked popularity of boys and flowers as a decorative motif was undoubtedly being its symbolic significance, which refers to the hope for numerous sons and abundance (p. 181).

For qingbai bowls carved with boys amongst scrolling vines, see one from the Kai-Yin Lo collection, included in the exhibition Bright as Silver, White as Snow, Denver Art Museum, Denver, 1998, cat. no. 39; and another published in Sekai toji zenshu, vol. 12, Tokyo, 1977, pls 162 and 163. Compare also qingbai meiping vases carved in a similar style with scrolling leaves and flowers against a combed background, for example in the Art Institute of Chicago, illustrated ibid., pl. 167; and in the Sichuan Provincial Museum, included in Zhongguo taoci quanji [The complete works of Chinese ceramics], vol. 8, Shanghai, 1999, pl. 179.

Estimation 2,500,000 — 3,000,000 USD / Sotheby's New York 2014.

坂本五郎與「目利」之藝

Jeffrey Hantover

據坂本五郎,Julia Meech 編,〈Eight Parts Full: A Life in the Tokyo Art Trade〉,《Impressions》號外,Japanese Art Society of

America,2011年

「古代青銅,擊而鳴之,可斷其歲。訛音千響,才得一要領體悟。」*

「訛音千響」雖非確數,難免虛誇,卻不失為謙遜之道, 用於鑑藏兼善之骨董商坂本五郎(圖一)身上,實合宜不過。日語中「目利」,指明辨善鑑之真知慧解,遠優於單純的眼力見識。坂本五郎律己以嚴,秉持「失敗乃成功之師」的宗旨,歷近七十寒暑,致思古藝,求達「目利」之境,以己為鏡,孜孜不息。他的自傳首於 1996年12 月《日本経済新聞》連載,憶述他初年於東京設店「不言堂」,進出東京美術俱樂部,參與倫敦、紐約、巴黎拍賣。當中所記,辛酸多於榮耀。懷着堅志大勇,勤學勵讀,憑藉他口中的「戰鬥精神」,歷年來購售不少中國、日本、韓國及中東古代藝術精品。

以魚躍龍門來形容坂本五郎的一生,實不為過。1923 年 9 月 11 日,坂本五郎出生才剛一天,關東發生大地震,重創橫濱, 瘡痍滿目。母親(圖二)在一片頽垣敗瓦中救出幼嬰、長子、 女兒,以及遭墮落橫樑壓折盤骨的夫婿。城裏火光彤彤,母親憑肩相扶受傷丈夫,又把五郎裹進衣懷,背其兄,牽其姊,領着全家脫離險地。不幸父親得傷後一病不起,八年後更與世長辭,留下遺霜獨力苦養七名子女。他們遷往東京以西四十公里的八王子市投靠親戚,過着艱辛的歲月,母親甚至要徒步至市郊購入雞蛋,然後連同糖果、蠟燭、火柴等雜貨,於屋前兜售。

1936年, 時坂本五十二歲,剛完成了六年小學,便於橫濱一所魚乾批發店當學徒。二戰末年,店舖生意一落千丈,坂本氏便重返八王子市,轉營舊衣買賣,並涉足與駐日盟軍的黑市交易。雖擅長判別海產好壞, 卻時被仿品所誤,未能洞察商品優劣,蹈襲覆轍,損失連連。 事隔六十載,他乃苦笑道:「這或許是我與贗品漫長鬥爭之開端。」坂本五郎承認當時他對古董「一竅不通」,但就是這樣,他別過舊衣買賣,離開危險的黑市交易,開始了他的古玩生涯。

坂本五郎穿梭於各個古董市場,尋覓有價值之品,此地買入,他地賣出。又為鑽研學問,走訪骨董店,專精覃思,盡其所能,購下大量藝術書籍。坂本氏購入的首幅畫作,後來才知乃仿模之品。

「若畏怯風險,那便絲毫沒有在 這個世界取勝的可能。」

且生意上未見小成,但他並未有輕言放棄。 事實上,這份不屈不撓的精神,坂本五郎一直堅守着,更成為他獨特的風格。因着與茶具店主的交情,坂本氏成為東京美術倶楽部的會員(1962 年 他更出任其理事長)。東京美術倶樂部的會籍極為尊貴,會員包括日本國內重要骨董商。回顧其古玩生涯,坂本氏皆求學於優秀且富經驗之藝商及藏家前輩。他曾寫道,指他「很榮幸擁有與人初次會面便可維持長久關係的天賦」。

1947 年夏,年屆二十四的坂本氏離開八王子市,往遷東京開店。中國有古諺云:「桃李不言,下自成蹊」。坂本氏引用之,商店名曰「不言堂」(圖三),日語有「不言」及「道」之意。 堂名巧取,玄機早種。坂本氏遠赴日本北部,購得伊萬里燒彩瓷盤,售予美國官兵,先下一城。也曾涉獵日本鐵茶壺買賣, 但礙於資金所限,僅能支付平俗之品。戰後初年,他四出覓尋瑰寶,每月有約二十天在外,足跡遍及各地。當然沒有私人座駕,歸途都是搭乘火車,拖着滿載便宜雜貨的行李,然後與在車站等他的兄弟會合,騎着從鄰近酒販借來的三輪工具車回家。坂本氏深知伊萬里燒僅屬「中庸之品」,高級藝商大都不屑涉獵。要躋身骨董英傑之列,專營古代藝術乃不二法門。

「我們的生意很像競技上之較量切磋,直取要害從不管用,相反曠日持久之戰才有望出奇制勝,凱旋而歸。只要有百折不移的堅持,機會便會降臨。」

坂本氏親身體會了鑑賞家之路的艱辛: 他曾買贗品,嘗過錯誤判斷市場而高買低售的滋味。起初以為經營之道,就是與私人藏家洽商雅翫小物買賣,將真正的傑作逸品售予藝商同儕,但不久便意識到此乃「人生最嚴重的失誤之一」,而「古董商成功之道正正在於與私人客戶洽售上乘佳器」。五十年代初,他苦心鑽研中國器物,歷盡挫敗,終得要領,藝品高下貴賤,慧眼立見。他嘗購入南宋官窰仿古琮式瓶(圖四,可謂其成功的開端,該器後售予鑑藏家広田松繁,最終捐贈東京國立博物館。他又曾買得酒井抱一之二扇折屏,上繪老松紫藤,後亦歸入広田松繁典藏,現已惠贈東京國立博物館。

「我為能自許乃戰後最勇敢的器物買家而驕傲。」

戰後,市場受限於佔領軍及日圓新鈔,加上寡學淺識,日本藝商一般對中國青銅器卻步。坂本氏雖承認他對吉金的了解「僅止於銅鐵之辨」,但他卻未有畏縮,終於以銳眼卓見勝出這場「 危險游戲」 。1968年,他用母親的名義饋贈東京國立博物館商周青銅共十件(圖五),以慶亞洲新翼啟幕, 此乃戰後最大規模的捐獻。2002 年,坂本氏又捐 380 件古銅器予奈良國立博物館, 熱善好施之心,表露無遺。所贈青銅現悉存於該館之「青銅器館(坂本コレクショ ン)」。

坂本氏在 John Figgess 爵士(圖六)的鼓勵下,對非茶道相關之漆器興趣漸濃。

John Figgess 爵士乃英國駐東京大使,後成為大衛德基金會的顧問,曾出任東方陶瓷學會及倫敦佳士得主席。坂本氏門利」,所得珍品包括北宋七瓣花式盤二件(圖七)及高麗王朝之嵌飾經盒,分別售予東京國立博物館及大英博物館。

「我逐步朝着要擁有日本以至全世界最頂級藝品的夢想邁 進。因此,歐洲人從前稱我為『小拿破崙』。」

1960年,坂本氏首度離國出遊,此後二十載,往返歐洲上百回,總是懷着無比的好奇和義無反顧的決心。他自知「不擅外語,除『ABC』外不懂英文」・遂「只好單憑『勇氣與直覺』,這就是我作買賣決定時的口號」。憑藉這些特質,坂本五郎在海外創下佳績。六十年代,參與倫敦拍賣的日本骨董商或藏家極少,坂本氏則是其中之一。他在倫敦購下嘉靖五彩魚藻紋罐(中等尺寸,現藏東京畠山記念館)的新聞, 為倫敦泰晤士報所報導。好友 John Figgess 爵士聞訊感悅,寫信道,戰後第一位見於該報的日本人名字乃首相吉田茂,坂本氏則是第二人。戰前,日本國內所知的官窰收藏僅止二器。 1970年,坂本氏得悉南宋官窰瓶將於倫敦拍賣,他以房屋作 抵押,飛赴英國參與。經過一輪熱烈競投,卻敗給友人仇焱之 (圖八)。兩年後,他終於成功投得重器,就其骨董事業而言, 若非巔峰,也屬高點。

時倫敦佳士得拍賣元代青花釉裏紅開光鏤空牡丹紋蓋罐在即。 為確保能投得這件當時認為是獨一無二之品(現知只有三例與 之相近,分別藏於大英博物館、河北省博物館及北京故宮博物 院),坂本氏前赴倫敦前,作好了出售所有藏品甚至藝店的準備。他最終旗開得勝,以 220,500 英鎊(500,000 美元)擷下 這個曾經用作雨傘架的元朝大罐,刷新當時亞洲藝術品的最高拍賣成交紀錄。即使是宣告成交過後,坂本氏心情仍未平伏, 並感到腹部劇痛,呼吸困難。不論當時還是現在,他從不認為付出的價錢過高。

他曾寫道:「佳品是昂貴的」。如果元代牡丹罐乃中國瓷器之后, 那數年後坂本氏從東京美術俱樂部購入之青花魚藻紋罐,獲他譽為瓷器之皇,實不為過。他曾在布魯克林博物館見過相近之青花魚藻紋罐,羡愛不已,但在他眼中, 二器相較,東京美術俱樂部瓷罐猶勝一籌。他奪魁後欣喜若狂,帶了瓷罐回家,抱之入浴,把歲月留下來的塵土洗滌乾淨,如上賓一樣與之共進晚膳。

「古董商人的生意,就是搜尋這些寶物,將其 公諸於世。」

七十年代,坂本五郎因健康理由正式退休,別過不言堂,遷居京都,但他並沒有從亞洲藝術的世界舞台退下來。至於他那「目利」的本領,乃多年經驗累積所得,所以更遑論會因之疏懶摒棄。坂本氏剛過九十大壽,依舊是世界活寶, 繼續以鑑賞家特有之第六感,預占藝品之「靈」和「氣」,澄察其「道」。

Sakamoto Gorō: A Life in Art

FAQ

1. Who is Sakamoto Gorō and what is he known for?

Sakamoto Gorō was a renowned Japanese antiques dealer, collector, and connoisseur with a career spanning nearly 70 years. He was renowned for his exceptional mekiki, an expert’s ability to judge authenticity that goes beyond a good eye. Throughout his life, he bought and sold some of the finest Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and ancient Middle Eastern art, amassing an impressive collection that included archaic Chinese bronzes, Southern Song Guan ware, and exquisite lacquer pieces.

2. What were some of Sakamoto Gorō’s early struggles and how did they contribute to his success?

Sakamoto Gorō's early life was marked by hardship, beginning with his family's displacement after the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. He learned the value of hard work and perseverance by helping his mother support their family. In his early antique dealing days, he encountered numerous setbacks, including buying fakes and misjudging market values. These experiences instilled in him a commitment to constant learning and a fearless approach to risk-taking, qualities that ultimately contributed to his success.

3. What was the significance of Sakamoto Gorō’s shop, Fugendo?

Sakamoto Gorō established his shop, Fugendo, in Tokyo in 1947. The name, meaning "does not call" and "path," symbolized his belief that good art would attract discerning buyers without the need for self-promotion. Fugendo became a prominent space for trading Asian art, and his success there solidified his reputation as a leading figure in the art world.

4. How did Sakamoto Gorō develop his expertise in art appraisal?

Sakamoto Gorō dedicated himself to continuous learning throughout his career. He frequented antique markets, meticulously studied art books, and cultivated relationships with experienced dealers and collectors. He was known for his ability to discern the "spirit" or "atmosphere" of an artwork, a quality that distinguished his mekiki and allowed him to recognize authentic pieces with remarkable accuracy.

5. What role did international travel play in Sakamoto Gorō’s career?

Starting in 1960, Sakamoto Gorō embarked on numerous trips to Europe, driven by his insatiable curiosity and determination. He participated in renowned auctions, significantly expanding his knowledge and network within the global art community. Despite language barriers, he navigated these international spaces with intuition and courage, earning recognition and respect from peers like Sir John Figgess and Edward Chow.

6. What is the significance of the Yuan Dynasty peony jar in Sakamoto Gorō’s career?

In 1972, Sakamoto Gorō acquired a Yuan Dynasty underglaze-blue and copper red-wine jar with openwork panels at a Christie's auction in London. He paid a then-record price of £220,500, demonstrating his unwavering belief in the value of exceptional art. This bold purchase cemented his reputation as a major player in the international art market and is believed to have contributed to the global boom in Chinese ceramics.

7. What significant contributions did Sakamoto Gorō make to museums?

Sakamoto Gorō was a generous donor to Japanese museums. In 1968, he donated ten Shang and Zhou bronzes to the Tokyo National Museum in honor of his mother, marking the largest postwar donation to the institution. Later, in 2002, he donated 380 archaic bronzes to the Nara National Museum, which now houses them in the dedicated Sakamoto Wing. These contributions highlight his commitment to sharing his passion for art and preserving cultural heritage.

8. What is the legacy of Sakamoto Gorō?

Sakamoto Gorō left behind a legacy that extends beyond his impressive collection and financial success. He is remembered for his relentless pursuit of knowledge, unwavering dedication to his craft, and generous spirit. His remarkable mekiki and intuitive understanding of art continue to inspire collectors and connoisseurs, solidifying his place as a legend in the world of Asian art.

Timeline of Events

1 September 1923:

Sakamoto Gorō is born in Yokohama.

The Great Kantō earthquake devastates Yokohama. Gorō's mother saves her family from their destroyed home.

1931:

Gorō's father dies from injuries sustained in the earthquake.

1936:

At age twelve, Gorō becomes an apprentice to a dried fish wholesaler in Yokohama.

1945:

World War II ends. Gorō's apprenticeship ends as his master's business is ruined. He returns to Hachioji and enters the used clothing business and black market trading.

Mid- to late 1940s:

Gorō begins dealing in antiques, starting with trips to various markets to buy and resell goods. He educates himself by studying art books and visiting antique shops. He begins frequenting the prestigious Tokyo Bijutsu Club.

Summer 1947:

Gorō, now 24, moves to Tokyo and opens his antique shop, Fugendo.

Late 1940s - early 1950s:

Gorō experiences early successes selling Imari-style wares to American soldiers and dealing in Japanese iron tea kettles.

He focuses on studying Chinese wares, honing his connoisseurship skills.

He purchases a Southern Song Guan ware cong and a Sakai Hoitsu screen, "Old Pines and Wisteria," both later donated to the Tokyo National Museum.

1950s - 1960s:

Gorō becomes a leading expert in archaic Chinese bronzes, a field many Japanese dealers avoided at the time.

1960:

Gorō makes his first trip abroad, beginning two decades of frequent travel to Europe for art dealings.

1962:

Gorō becomes a director of the Tokyo Bijutsu Club.

1964:

Gorō gains international recognition for his purchase of a polychrome enameled Jiajing jar in London, becoming only the second Japanese person mentioned in the London Times after the war.

1968:

Gorō makes a major donation of ten Shang and Zhou bronzes to the Tokyo National Museum in honor of his mother for the opening of their Asian wing.

1970:

Gorō attends an auction in London to bid on a Southern Song Guan vase but loses to Edward Chow.

1972:

Gorō purchases a Yuan Dynasty underglaze-blue and copper-red wine jar (guan) at Christie's in London for £220,500, the highest price paid for an Asian artwork at auction at the time.

Mid-1970s:

Gorō purchases a Yuan underglaze cobalt-blue wine jar with fish and aquatic plants, which he considers his greatest acquisition.

Late 1970s:

Gorō formally retires from Fugendo due to health reasons and moves to Kyoto. He continues to be involved in the world of Asian art.

2002:

Gorō donates 380 archaic bronzes to the Nara National Museum, where they are housed in the Sakamoto Wing.

Present:

Gorō, passed away, is recognized as a leading figure in the world of Asian art and connoisseurship.

Cast of Characters

Sakamoto Gorō:

The central figure of the timeline. An acclaimed art dealer, collector, and connoisseur of Asian art, particularly known for his expertise in Chinese ceramics and archaic bronzes. He rose from humble beginnings to become a leading figure in the international art world.

Sakamoto Gorō's Mother:

An unnamed but significant figure in Gorō's life. She showed great strength and resilience in saving her family during the Great Kantō earthquake and raising her children alone after her husband's death. Gorō attributes his success in part to her influence and honors her with his major art donations.

Sir John Figgess:

British diplomat, art expert, and friend of Gorō. He encouraged Gorō's interest in lacquerware and celebrated his achievements, including his purchase of the Jiajing jar. He served as an advisor to the Percival David Foundation, president of the Oriental Ceramics Society, and director of Christie's London.

Edward Chow:

A fellow art connoisseur who outbid Gorō for a Southern Song Guan vase in 1970.

Hirota Matsushige:

A connoisseur who purchased the Southern Song Guan ware cong and the Sakai Hoitsu screen from Gorō and later donated them to the Tokyo National Museum.

Sakai Hoitsu:

A Japanese artist known for his screen paintings, including "Old Pines and Wisteria," purchased by Gorō and later owned by Hirota Matsushige.

Comments