宋代筆記 vol.95 小聽颿樓1020万钧窑成交:清宮鈞窰玫瑰紫釉渣斗式花盆 「三」字款 - An Exceptional Junyao Purple-Splashed Zhadou-Form Flowerpot, Canton Collection.

- SACA

- Oct 4, 2024

- 21 min read

Updated: Oct 27, 2024

小聽颿樓潘家的傳世作品,相信來自清宮。2018年一件Eskenazi、賽克勒舊藏的乾隆舊藏藍色鈞窯花盆在嘉德北京拍出4887.5萬元,創造本品種的世界紀錄。

這件顏色更為華美高貴的紫紅色作品,傳承顯赫,估價僅為800-1500萬港元,十分保守。

500起拍、直接到700万、750万、800万、820万、850万落槌!成交价1020万港元。

參考《宋代筆記 vol.94 帝王的花圃:4887.5萬的鈞窯花盆與清宮鈞窯的宋明之爭 - Emperor's Garden, and the Dating of Imperial Jun Wares.》

鈞窰玫瑰紫釉渣斗式花盆 底刻「三」字

An exceptional Junyao purple-splashed zhadou-form flowerpot, Ming dynasty, early 15th century

Estimate

8,000,000 - 15,000,000 HKD

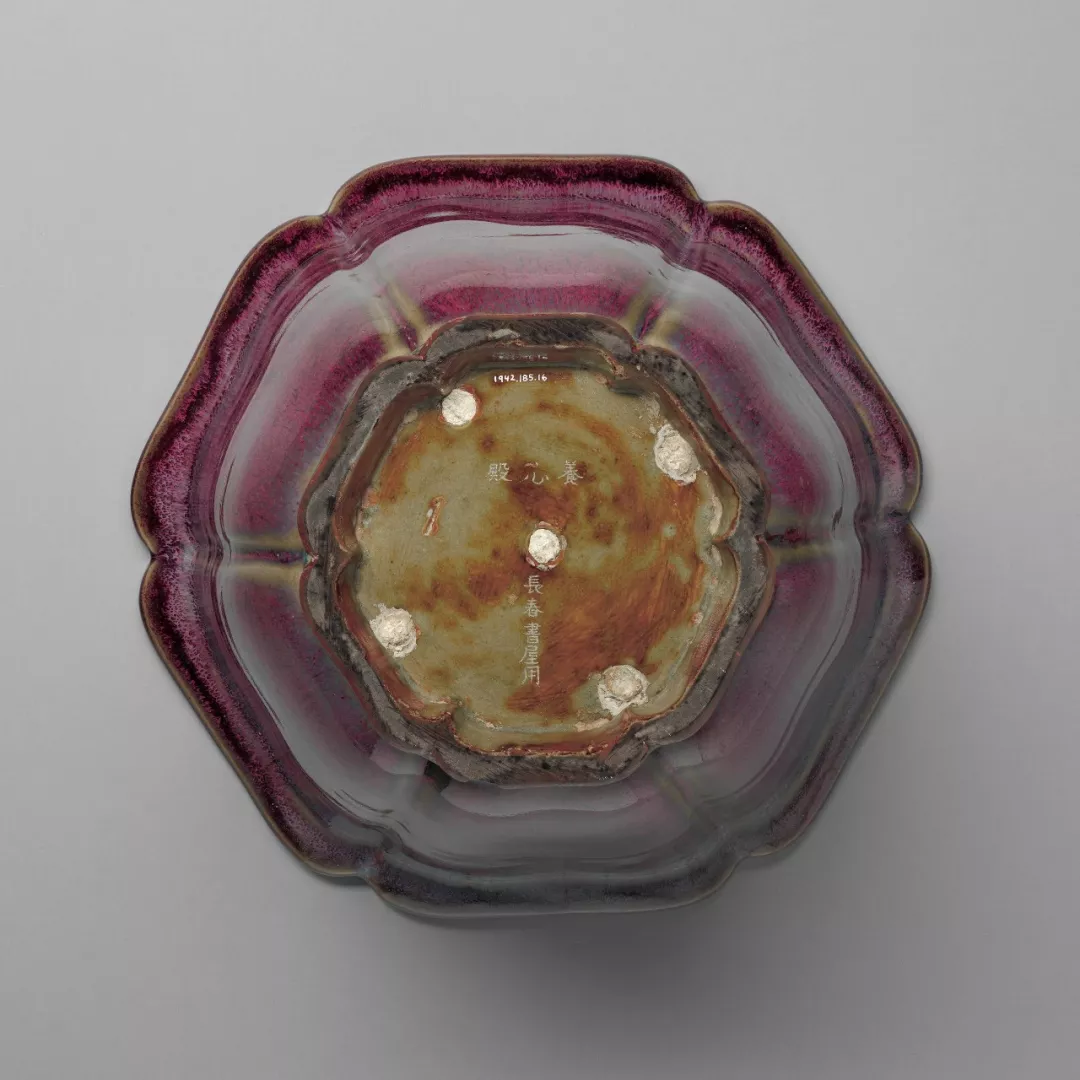

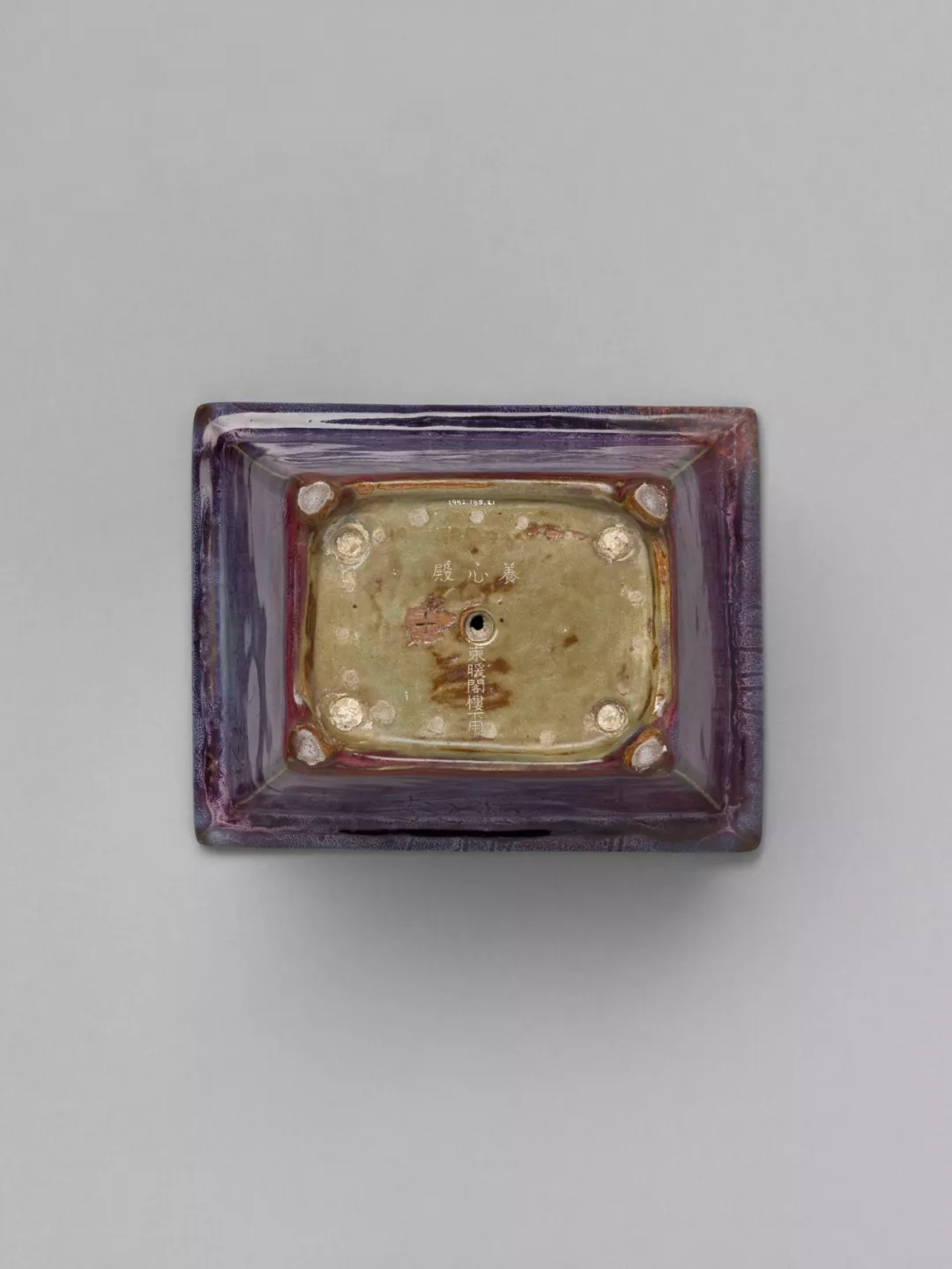

sturdily potted with a globular body rising from a splayed foot to a flared mouth, the elegant well-proportioned body applied with a thick opalescent glaze in an alluring blend of purple and blue with characteristic 'earthworm tracks' pattern, the interior applied with an even sky-blue glaze, the exterior further accentuated with washes of mottled purple, transmuting to a vibrant crimson hue around the foot and thinning to a softer mushroom tone at the rims, the base covered with an olive-brown wash and inscribed with a numeral san (three)

d. 23.5

Provenance

Collection of Pan Baoheng (1862-1927), grandson of Pan Zhengwei, thence by family descent and entered the Canton Collection, Hong Kong.

潘寶珩(號佩如,潘正煒之孫,1862-1927年)收藏,此後家族傳承,經小聽颿樓遞藏

Exhibited

In Pursuit of Antiquities: Thirty-fifth Anniversary Exhibition of the Min Chiu Society, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1995-1996, cat. no. 96.

《好古敏求:敏求精舍三十五週年紀念展》,香港藝術館,香港,1995-1996年,編號96

天外綺色

康蕊君

中國御製工藝品發軔於永樂一朝。回溯歷史,臺案器什及殿堂傢具素來廣為皇室需求,或留作己用,或撥作賞賜。數百年間,瓷器等工藝品作坊為歷代宮廷供給所需,獲宮廷青睞者亦受帝王資助。永樂帝出資之餘,亦於敕造之物附自身印記,乃前朝未見。舉國上下,精粹作坊皆被天子招納,出品專供宮廷。永樂帝更開先河施加年款,起初年款多見於御製佛器。永樂治下,製瓷技法繼古開今,新器標準乃得拔高。此前,器形、紋飾全賴工匠技藝,永樂帝則對整體構思嚴加把控,然把控雖嚴,此朝窰業卻蓬勃發展,絕非千篇一律。

永樂御製品林林總總,用於內廷之外者不在少數:御製鎏金銅佛造像贈予西藏,御製漆器傳入日本,御製瓷器銷往波斯等西亞諸國。長久以來,研究以為此朝御瓷悉數出自江西景德鎮,然近年發現另有兩處窰口應亦是御瓷出處:浙江龍泉窰與河南鈞台窰。此朝官製青瓷或主供外銷,與青花無異,而官製鈞瓷則未見流出中國,當為內廷專用。

鈞瓷花器大多底部刻有數字,從一到十,自成一體,本件亦屬此類。相比之下,鈞窰盌、盤、瓶等器無此規律。與宋、金、元其他瓷器不同,鈞瓷花器須以模製胎,成器不失毫厘,可見官造之嚴謹。若論風格、品質,此類花器產燒時間甚短,尚無遞嬗。十五世紀前,未見此等官製規格,至各窰口依旨產燒,花器形制、尺寸方有明確。永樂帝自南京遷都北京,新建宮室,亟需瓷器陳設,是故大量產燒。為迎天子,紫禁城於1417年動工,1420年基本竣工,自此皇室遷居1。

本件器形為渣斗,古已有之,宋代時興,原用於宴桌盛裝渣滓。本件底部開孔,可疏水通流,乃作花盆。除花盆、花樽外,鈞台窰僅產燒少量食器,如盌、盤及高足盌等,與明初景德鎮所產相類,然產量截然不同;景德鎮產瓷秀巧,常為桌面用器,而鈞窰胎體厚重,更宜園藝擺弄。時至宣德,景德鎮渣斗仍為渣滓容器,底部密封2。

底部開孔後,盆內可填入土壤育植花卉,置於室內時,盆底須添盆托以盛盆孔滲水。若盆呈長方、六方或菱花式,盆托隨形。若遇圓形者,有如此件,則以鈞瓷名品鼓釘三足盆托為配。器底數字疑與尺寸相關,然刻字緣由尚不明晰。有說以數字匹配花盆與盆托,或對應成器與匣鉢,亦有說以數字標示等級,其時社會等級森嚴,此說不無道理。

學界一致認為此類花盆為官鈞,然就斷代仍莫衷一是。明初斷代已受普遍認可,代表學者有台北故宮余佩瑾及上海博物館陸明華3。另有觀點較為保守,傾向金元斷代;亦有學者遵循傳統,以北京故宮為首,斷代北宋4。

金元說可能性微乎其微。此類花盆屬宮廷收藏,自十八世紀尤受宮廷賞識,而宮廷收藏中罕有金元外族遺珍。北宋說乃因窰址附近該地層出土鈞窰陶範,用於宣和朝鑄幣,但此說亦招反駁5。

明代以前,文字記載不見鈞瓷6。窰址發掘報告乃依地層斷代北宋。鈞台窰址地層有五,發掘結果驚人7。最上層為明代,不作歷朝細分,最下層為唐代,居中三層皆斷為北宋,分早、中、晚三期。官鈞瓷出土於明代地層之下,即所謂「北宋晚期」地層。金、元乃至明初地層且不細考。此「北宋晚期」地層中亦有其他發現,如磁州窰彩繪陶瓷,又將斷代指向元至明初8。

雖斷代紛然,官鈞瓷器之精耀雋美則受一致推崇。本件底刻數字,釉色似流霞幻彩,為官鈞經典。釉層緻密,光線折射呈天藍,釉藥含銅,氧化還原呈赤紫,濃淡斑駁,氤氳漫染如霧嵐,是為鈞台窰獨創釉色。永樂一朝,景德鎮窰試新出奇,然所產皆不可與之媲美。官鈞釉面有不規則線狀釉痕,中國稱「蚯蚓走泥紋」,可見本件,或為出窰後冷卻過程中形成,恰如冰裂紋之於官青釉,本是釉中瑕疵,反成就官鈞瓷器獨有之美。

雍正帝位居親王時便已鍾情於官鈞瓷器。《雍正妃行樂圖》中可見一鈞窰玫瑰紫菱口花盆及隨形盆托,盆中育花,置於室內一美貌女子身側,該圖軸為獻雍親王而作(圖一)9。繼位後,雍正帝將鈞瓷原件送往景德鎮,御窰仿燒,成器頗似——台北故宮藏有一花盆及盆托,與圖軸所繪如出一轍,皆帶雍正年款——亦衍生新品類,西洋稱窰變釉(圖二)10。明初官鈞釉氣韻莫測,凝眸端視,神思如載雲霞而臨天外,縱有景德鎮於三百年後取得成果,官鈞妙趣仍難企及。

此式官鈞花盆存世若干,數字、釉色各不相同,可比數例,藏故宮博物院,北京,錄《鈞瓷雅集・故宮博物院珍藏及出土鈞窰瓷器薈萃》,故宮博物院,北京,2013年,圖版73、74、106,及一例,長頸截短,圖版107。另比二例,同為「三」字渣斗式,藏哈佛藝術博物館,該館於1942年獲 Ernest B. 與 Helen Pratt Dane 伉儷捐贈大批官鈞收藏:其一(館藏編號:1942.185.38),釉色變化與本件甚似,其二(館藏編號:1942.185.37),釉色分層,頸為天藍腹為紫。鈞台窰址有盆底殘件出土,原件為渣斗式或仰鐘式,載《禹州鈞台窰》,鄭州,2008年,彩圖9-13;另有殘件,可判定為渣斗式花盆底,錄前述《鈞瓷雅集》,圖版75。

1 牟復禮、崔瑞德,《劍橋中國明代史》,上卷,劍橋,1988年,頁239-41。

2《明代宣德官窰菁華特展圖錄》,故宮博物院,台北,1998年,編號17、18。

3 見《雍正:清世宗文物大展》,故宮博物院,台北,2009年,頁228;2024年6月12日,巴黎吉美博物館單色釉學術研討會亦有提及。西方學者對北宋斷代反駁已久,見康蕊君,〈On the Forefront of Research: Breakthrough Lectures at the Oriental Ceramic Society〉,《美成在久》,2021年11/12月,頁32-3。

4 如《故宮陶瓷館》,卷5,北京,2021年,及《鈞瓷雅集・故宮博物院珍藏及出土鈞窰瓷器薈萃》,故宮博物院,北京,2013年,將大多數(非全部)官鈞瓷器定為北宋。

5 李寶平,〈Numbered Jun Wares: Controversies and New Kiln Site Discoveries〉,《東方陶瓷學會彙刊》,卷71,2006-7年,頁65-77。

6 馮先銘,《中國古陶瓷文獻集釋》,台北,2000年,頁74-6。

7《禹州鈞台窰》,鄭州,2008年,有圖表,頁16。

8 出處同上,頁38,圖十七及彩圖40、41。

9《China. The Three Emperors 1662-1795》,皇家藝術研究院,倫敦,2005-2006年,編號173右下。

10《雍正:清世宗文物大展》,前述出處,編號II-54、55及II-52、53。

Ethereal Colours

Regina Krahl

The concept of Chinese imperial works of art goes back to the reign of the Yongle Emperor (r. 1403-1424). Throughout history, every court required table wares and palace furnishings for its own use or to bestow as gifts. Ceramic and other workshops had for centuries supplied the various courts with their goods, and the courts may have patronised favourite providers. The Yongle Emperor took patronage a step further, as he seems to have identified more directly with the works he commissioned than the rulers before him. He took over some of the best workshops in his empire and had them produce more or less exclusively for the court; and he started the fashion of having his reign name inscribed on objects, albeit at first mainly on objects intended for Buddhist ritual. He demanded much increased and more consistent standards of quality than had been available with the traditional methods of ceramic manufacture; and he expected much more carefully conceived overall designs than had been possible when forms and ornaments were dependent on the potters’ dexterity. Although ceramic production in the Yongle period was clearly subject to strict supervision and control, this did not limit variety or stifle innovation.

The group of Jun flower vessels, mostly inscribed on the base with numbers from one to ten, to which the present piece belongs, form a closely coherent group. They are distinctly different from the general pool of Jun bowls, dishes and vases that are characterised by the haphazard variations of hand-made ceramics. Unlike the typical ceramic wares of the Song (960-1279), Jin (1115-1234) and Yuan (1271-1368) periods, they were all shaped in twin moulds. They are all finely made and exactingly finished, displaying the precision guaranteed by government surveillance. They do not seem to have undergone any development, either stylistically or qualitatively, but seem to have been made within a very short span of time. Imperial orders of such calibre are not known from before the early fifteenth century. The kilns must have had a distinct brief to provide flower vessels in a prescribed range of shapes and sizes. The most obvious occasion for such a large commission of wares for display would have been the Yongle Emperor’s move of the capital from Nanjing to Beijing, where new palaces were constructed and had to be fitted out. Work on the Emperor’s new residence in the Forbidden City took place largely in 1417 and by 1420 the main construction projects had been completed, allowing the court to be transferred.1

Zhadou, as the present shape is known, is an ancient form that was popular in the Song dynasty, but at the time probably as a refuse vessel to collect dregs at table. In the present form, with its base pierced for drainage, it has been turned into a flower pot. Apart from flower pots and vases, only a small number of food vessels seems to come from the same Juntai production line, in the form of bowls, dishes and stem bowls, which echo early Ming (1368-1644) shapes from Jingdezhen. They don’t seem to have been made in similar quantities, however, since the delicate porcelain of Jingdezhen was probably preferred for table wares. The sturdier Jun stoneware body, on the other hand, must have seemed better suited to the rougher handling planters were subjected to. At Jingdezhen, the zhadou shape was in the Xuande period (1426-1435) still produced as a container with a closed base.2

With their pierced bases, these vessels were meant to be filled with earth and planted with flowers and, when used indoors, required another vessel underneath to collect water draining through the holes. The angular and barbed forms have supporting basins of matching shape. For circular flower pots, such as the present vessel, the only suitable type of receptacle would have been the well-known tripod basins with applied bosses reminiscent of drum nails. While the inscribed numbers do seem to relate to sizes, their purpose is unclear. They might have been added to match flower pots with supporting basins of the right size, or to find saggars of suitable dimension, or else to clearly display some kind of ranking, which in a society where all benefits were strictly graded according to rank would not be surprising.

In the scholarly community, there seems to be unanimity that these outstanding vessels are imperial. In terms of dating, however, there is still no general agreement. An early Ming attribution is now widely accepted, for example, by Yu Peijin at the Palace Museum, Taipei, and by Lu Minghua at the Shanghai Museum.3 There is a group of scholars, however, that prefers a more cautious dating to the Jin or Yuan dynasties; and another group, mainly at the Palace Museum, Beijing, which supports the traditional dating to the Northern Song period (960-1127).4

The former attribution would seem unlikely. We know that these vessels were well represented in the imperial collection, where wares from the foreign-ruled Jin and Yuan dynasties are scarce, since they attracted imperial attention already in the eighteenth century. The dating to the Northern Song dynasty was originally based on a mould made of Jun ware clay found nearby, that was believed to have been used to mint coins of the Xuanhe period (1119-25); this evidence has in the meantime been refuted.5

No textual evidence of Jun wares is known prior to the Ming dynasty.6 The excavation report of the kiln site supports a Northern Song dating based on stratigraphy. The interpretation of the five strata at the Juntai excavation site is, however, rather surprising.7 Distinguished have been a Ming stratum – not dated more precisely – at the top, a Tang (618-907) stratum at the bottom, and three strata in between. These three have all been attributed to the Northern Song dynasty, to an early, a middle and a late period. The imperial Jun wares were discovered directly below the ‘Ming’ stratum, in the layer labelled ‘late Northern Song’. Jin, Yuan, and possibly early Ming layers are not taken into account. Other finds from the so-called ‘late Northern Song’ stratum, such as painted Cizhou-type stonewares, for example, clearly suggest a Yuan or early Ming date.8

What is undisputed, however, is the exceptional beauty and quality of these imperial, or official, ‘guan Jun’ wares, and the present vessel, with its striking variegated glaze tones and deftly incised number is a prime example. With its opalescent optical blue caused by refraction of light where the glaze layer is thick, its intense purple tones derived from copper, and its finely mottled structure that gives the impression of surface texture and depth, this extraordinary glaze was a unique development of the Juntai kilns. Nothing comparable could be produced at the Jingdezhen kilns, although they experienced a peak of ingenuity and experimentation in the Yongle period. The streaks in Jun glazes known in China as ‘earthworm tracks’ – distinctly visible on the present piece – which can appear during cooling after firing, much like the crackle in celadon glazes, became an admired trademark of these imperial wares, although they represented basically a flaw in the glaze.

The Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723-1735) seems to have fallen in love with these vessels while still Prince. A bracket-lobed purple-glazed Jun jar and matching basin planted with flowers can be seen in an interior featuring a beautiful lady, that was painted for him (fig. 1).9 As Emperor he sent originals to the kilns at Jingdezhen, which resulted in close copies – a flower pot and support as depicted in that painting, both inscribed with Yongzheng reign marks, are in the Palace Museum, Taipei – as well as in a related new glaze type, known in the West as flambé (fig. 10).10 Neither of these Jingdezhen creations succeeded, even three hundred years later, to recreate the mysterious aura of the Ming glazes that might transport a sensitive viewer into ethereal realms.

Imperial Jun flowerpots of this form, with various numbers and different glazes have been preserved, for example, in the Palace Museum, Beijing, see Jun ci ya ji. Gugong Bowuyuan zhencang ji chutu Junyao ciqi huicui/Selection of Jun Ware. The Palace Museum’s Collection and Archaeological Excavation, Palace Museum, Beijing, 2013, pls 73, 74, 106, and with cut-down neck, pl. 107. Two jars of the same form and number are in the Harvard Art Museums, which in 1942 acquired the largest collection of imperial Jun wares, assembled by Ernest B. and Helen Pratt Dane: one of them (acquisition no. 1942.185.38) very similar in its colour range, the other (acquisition no. 1942.185.37) with the glaze colours separated, showing a light blue neck and purple body. Many base fragments from jars of the present shape or else of inverted bell shape have been excavated from the kiln site, see Yuzhou Juntai yao/The Juntai Kilns in Yuzhou, Zhengzhou, 2008, col. pls 9–13; some specifically identified as coming form zhadou-shaped vessels are illustrated in Jun ci ya ji, op.cit., pl. 75.

1 Frederick W. Mote and Denis Twitchett, The Cambridge History of China, vol. 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368 – 1644, part I, Cambridge, 1988, pp. 239-41.

2 Mingdai Xuande guanyao jinghua tezhan tulu/Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Selected Hsüan-te Imperial Porcelains of the Ming Dynasty, Palace Museum, Taipei, 1998, cat. nos 17 and 18.

3 See Yongzheng. Qing Shizong wenwu dazhan/Harmony and Integrity. The Yongzheng Emperor and His Times, Palace Museum, Taipei, 2009, p. 228; and expressed at a symposium on monochrome wares at the Musée Guimet, Paris, 12th June 2024. Western scholars had long argued against a Northern Song date; see Regina Krahl, ‘On the Forefront of Research: Breakthrough Lectures at the Oriental Ceramic Society’, Orientations, November-December, 2021, pp. 32-3.

4 E.g. Gugong taoci guan/Ceramics Gallery of the Palace Museum, 5 vols, Beijing, 2021; in Jun ci ya ji. Gugong Bowuyuan zhencang ji chutu Junyao ciqi huicui/Selection of Jun Ware. The Palace Museum’s Collection and Archaeological Excavation, Palace Museum, Beijing, 2013, most (but not all) of the imperial Jun wares are labelled Northern Song.

5 Li Baoping, ‘Numbered Jun Wares: Controversies and New Kiln Site Discoveries’, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 71, 2006-7, pp. 65-77.

6 Feng Xianming, Zhongguo gu taoci wenxian jishi/Annotated Collection of Historical Documents on Ancient Chinese Ceramics, Taipei, 2000, pp. 74-6.

7 Yuzhou Juntai yao/The Juntai Kilns in Yuzhou, Zhengzhou, 2008, with a table, p. 16.

8 Ibid., p. 38, fig. 17 and col. pls 40 and 41.

9 China. The Three Emperors 1662-1795, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2005-6, cat. no. 173 bottom right.

10 Yongzheng. Qing Shizong wenwu dazhan, op.cit., cat. nos II-54 and 55; and II-52 and 53.

帝王的花圃 - 鈞窯的宋明之爭

Emperor's Garden - A Junyao's fate

2018年,嘉德拍賣通過保稅拍賣的方式,在北京拍賣了一件著名古董商Eskenazi經手的傳世鈞窯花盆,成交紀錄為4880萬人民幣。

在北京拍賣宮廷概念的器物,一直都有不俗的表現,這件Eseknazi鈞窯展覽封面的器物,也自然不在話下,4880萬人民幣是一個好價格。歸根到底,主要原因可能是:1、清宮傳世;2、Eskenazi傳承顯赫;3、耿寶昌老人視頻強和支持。

雖然學界對這類鈞窯的年代一直頗有爭議,一說明代,一說宋代,但也阻擋不了藝術的熱情和買家的決絕。

In 2018, Guardian Auctions sold a heirloom Junyao flowerpot with an impeccable provenance by the renowned antique dealer Eskenazi through an auction in Beijing, with a record sale of RMB 48.8 million.

Auctions in Beijing of objects with a palace concept have always performed well, and this Eseknazi Jun Exhibition cover piece was naturally no exception, with RMB 48.8 million being a good price even by today's standard.

The main reasons may be: 1, the Qing dynasty heritage; 2, Eskenazi heritage prominent; 3, Geng Baochang confidence in his video support.

Although the academic community has been quite controversial about the age of this type of Jun kiln, one said the Ming Dynasty, the other said the Song Dynasty, but also can not stop the enthusiasm of the art and the buyer's determination.

拍賣會中國嘉德2018年秋季拍賣會

年代明初

尺寸H 18.5 cm (7 1/4 in) D 20 cm (7 7/8 in)

成交价: RMB 48,875,000

“六”字(已磨)

建福宮 凝暉堂用

本件拍賣標的處於保稅狀態下

[來源]

1.弗蘭克•卡羅, 盧芹齋繼任者(Frank Caro),美國;

2.亞瑟•M•賽克勒(Arthur M. Sackler),美國;

3.埃斯肯納齊(Eskenazi),英國。

[展覽]

1.1965年,哥倫比亞大學,紐約;

2.中國藝術3500年:亞瑟•M•賽克勒藏中國陶瓷,1987年,以色列博物館,耶路撒冷;

3.鈞窯,2013年,埃斯肯納齊,倫敦。

[出版]

2013年,埃斯肯納齊《鈞窯》,頁 86。

花盆尊式,撇口,束頸,鼓腹,圈足,厚胎厚釉,施釉及底,裹足刮釉。器身通體呈天青色調,器腹及內底泛出淡淡海棠紫暈,口沿及足牆外側釉水稀薄處,淺現胎骨色,底足施釉極薄,視為橄欖綠色。器底於入窯燒制前刻“六”字款(已磨),乾隆朝時加刻“建福宮 凝暉堂用”殿閣款。

與本次拍賣的鈞窯花盆同器型且同刻“六”字的例子有五例,其中三例為天青釉,另外兩例為海棠紫釉。天青釉例一,與本次拍品於2013年共同展出於埃斯肯納齊(Eskenazi)亞洲藝術周鈞窯大展;例二,大維德(Sir Percival David)於1937年購自山中商會,現展於大英博物館;例三,底刻“建福宮 敬勝齋樓下用”,是除本次拍賣的鈞窯花盆外唯一一件刻有殿閣款的“六”字款尊式花盆,現藏於台北故宮博物院。另兩例海棠紫釉的,分別保存於哈佛大學賽克勒美術館,及故宮博物院(北京故宮)。公私收藏中,刻有“建福宮 凝暉堂用”的鈞窯花盆,僅有一例,為一玫瑰紫釉四方式花盆,現藏於台北故宮博物院。

帝王的傳承 (建福宮 - 凝暉堂)

建福宮

帝王的宮殿,英文名都很好聽。建福宮又叫The Palace of Established Happiness,1740年,作為他的一個新的居所,29歲的乾隆命人在紫禁城的西北角修造建福宮。作為一個年輕的皇子,他又曾住在他父親雍正建造的“重華宮”(The Palace of Double Glory),繼位之後,又搬到了“養心殿”(The Hall of Mental Cultivation)。

建造建福宮,乾隆的意圖是建造一個世外桃源,一個暫離繁重公務、帝王職責的娛樂區。花園難免是一個娛樂的核心,營造一個考究的精緻花園變得十分合理 - 建福花園,布滿假山、亭台、小橋流水… 構建一個微觀自然世界,作為中國傳統文人的精神樂園,根深蒂固,有著深遠的歷史。

Jianfu Palace

The Jianfu Palace is a palace of the emperor, with an auspicious meaning, also known as The Palace of Established Happiness, in 1740, the 29-year-old Qianlong ordered the construction of the Palace of Established Happiness in the north-west corner of the Forbidden City as a new residence for him. As a young prince, he lived in the Palace of Double Glory, built by his father, Yongzheng, and then moved to the Hall of Mental Cultivation after his accession to the throne.

In building the Jianfu Palace, Qianlong's intention was to create a paradise, a recreational area temporarily removed from the heavy burden of official duties and imperial responsibilities. Inevitably, the garden was a centre of entertainment, and it made sense to create an elaborate and refined garden - the Jianfu Garden, full of rockeries, pavilions, bridges and waterfalls... a microscopic world of nature that has deep roots and a profound history as a spiritual paradise for the traditional Chinese literati.

凝暉堂

在建福宮中,有兩處地方是乾隆用來賞玩珍寶的,分別是:靜怡軒(The Pavilion of Tranquil Ease),還有凝暉堂(The Hall of Concentrated Radiance)。靜怡軒是建福宮中尤為重要的建築,也就是在這裡,乾隆存放了赫赫有名“乾隆四美”珍藏繪畫,它們分別是《女史箴圖》(大英博物館)、《 瀟湘臥游圖》(東京國立博物館)、《蜀川勝概圖》(弗利爾博物館)、《九歌圖》(國家歷史博物館),其中後三幅來自北宋畫家李公麟。

Ninghui Hall

In the Jianfu Palace, there are two places where Qianlong used to appreciate treasures: The Pavilion of Tranquil Ease and The Hall of Concentrated Radiance. The Pavilion of Tranquil Ease is a particularly important building in the Jianfu Palace, and it was here that Qianlong kept the famous ‘Four Beauties of the Qianlongs’ collection of paintings, which were the ‘Proverbs of the History of a Woman’ (British Museum), the ‘Reclining Tour of Hsiao Hsiang’ (National Museum of Tokyo), the ‘Scenic View of Shu Chuan’ (Freer Museum), and the ‘Nine Songs’ (National Museum of History), the last three of which were the most important of all. The last three paintings are by the Northern Song painter Li Gonglin.

在凝暉堂中,存放著一組極為重要的“三友”主題的繪畫,有十八學士,有宋元明畫家繪制的梅花等,乾隆命名”三友軒“。松竹梅歲寒三友常用來比喻文人雅士的清高節氣,三友圖以象徵常青不老的松、象徵君子之道的竹和象徵冰肌玉骨的梅組成。

所以就是在這個凝暉堂中的三友軒,乾隆度過了許多美好的時光。實際上在他退休後居住的寧壽宮中,也有一處“三友軒”,證明這處地方在他心中的位置極為重要。也就是凝暉堂,乾隆心中最重要的地方,這件鈞窯花盆被珍藏、賞玩,而且不是被一般人,是乾隆本人。

In the Hall of Contemplation, there is a very important group of paintings on the theme of ‘Three Friends’, with eighteen scholars and plum blossoms painted by Song, Yuan and Ming artists, which the Qianlong emperor named the ‘Pavilion of Three Friends’. Pine, bamboo, plum and the three friends of the cold are often used as a metaphor for the elegance of the literati, the three friends of the picture to symbolise the evergreen pine, symbol of the gentleman's way of bamboo and symbol of the icy skin and jade bone of the plum composition.

So it was in this Three Friends Pavilion in the Hall of Concealed Glory that Qianlong spent many good times. In fact, in the Ning Shou Palace, where he lived after his retirement, there was also a ‘Pavilion of Three Friends’, which proved the importance of this place in his heart. It is also the Ninghui Hall, the most important place in Qianlong's heart, where this jiun kiln flowerpot was treasured and admired, not by the general public, but by Qianlong himself.

建福宮在1920年的一場大火中毀滅, 我們現在只能想象凝暉堂中的珍寶,家居陳設,或許其中一個紫檀案上,就擺放著這件凝暉堂用鈞窯花盆。另外一件同款,銘建福宮凝暉堂,在台北故宮博物館。

另外,哈佛大學博物館在1942年接受了一批鈞窯捐贈,現在擁有大量的這類花盆類鈞窯器物(也稱官鈞),其中有一件,也銘有“建福宮 - 三友軒用”。

The Jianfu Palace was destroyed in a fire in 1920, and we can only imagine the treasures in the Hall of Concealed Favour, the furnishings, and perhaps one of the rosewood cases on which this Junjun kiln flowerpot from the Hall of Concealed Favour was placed. Another example of the same type, inscribed in the Hall of Contemplation, is in the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

In addition, the Harvard University Museums in 1942 accepted a number of Jun kiln donations, and now has a large number of such flower pots Jun kiln wares (also known as official Jun), one of which, also inscribed ‘Jianfu Palace - Three Friends Xuan with’.

這批所謂花盆類,清宮舊藏的花盆年代一直有爭議。有宋代說,也有明代說。台北故宮許多器物的定義上,還是保持宋代;ESKENAZI已經定在了明代;而耿寶昌老先生,在看到這件凝暉堂鈞窯的時候,興奮的像小孩子一樣,拍手說:「如果出書,就寫宋。」

This dating of Jun flower pots in the Qing Palace imperial collection has been a subject of controversy, over whether they are Song or Ming Dynasty. Major instituations around the world including ESKENAZI has favored the Ming Dynasty; whereas Geng Baochang, when asked about the dating of the auction piece, excited as a child, clapping his hands and said firmly: Just write, Song Dynasty.

鈞窯花器的宋明之爭

宋代說

中國歷史上,無數典籍因戰亂動蕩永遠失去。許多學術問題之所以難解,正因無法在流傳下來的史料記載、書畫文本中,找到官鈞窯起源的確鑿記載。

一直以來,古董商、收藏家、學者專家都相信,官鈞窯制於北宋末年,乃宋徽宗用來種花,置於御花園「艮岳」以賞奇石、觀名花所用。 1974年,河南省禹州鈞台窯址的考古發掘,亦引證了鈞窯始於宋代之說。

明代說

2004年,深圳考古所在河南省禹州一個藥廠遺址,作搶救式發掘,以瓷片的器形對比,推論官鈞窯是明代初期所制。隨後眾多海外博物館也把年份由宋改為明初。大型拍賣行為保障買賣雙方,也多把官鈞斷代為元末明初。

The Song-Ming Controversy over Jun Kiln Flower Ware

Song Dynasty

In Chinese history, countless books have been lost forever due to war and turmoil. The reason why many academic problems are difficult to solve is that it is impossible to find a solid record of the origins of the Official Jun Kiln in the historical records, paintings and calligraphic texts that have been handed down to us.

For a long time, antique dealers, collectors, scholars and experts have believed that the kiln was made in the late Northern Song Dynasty, and was used by Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty to grow flowers, and was placed in the Imperial Garden ‘Burgundy Mountain’ to appreciate the strange stones and view famous flowers. In 1974, the archaeological excavation of the Juntai kiln site in Yuzhou, Henan Province, also proved that the kiln began in the Song Dynasty.

Ming Dynasty

In 2004, the Shenzhen Institute of Archaeology conducted a rescue excavation at the site of a pharmaceutical factory in Yuzhou, Henan Province, and deduced that the kilns were made in the early Ming Dynasty by comparing the shapes of the ceramic pieces. Subsequently, many overseas museums changed the year from Song to early Ming. Large auction houses in order to protect the buyer and seller, but also more of the official kwan to the end of the Yuan Dynasty and the early Ming Dynasty.

哈佛大學博物館

同款器物

哈佛大學藏有同款鈞窯花盆一共八件(其中一件殘器),但沒有一款有帶銘文,所以此次的這件,非常難得。並不是所有的同類的花盆都會被銘刻。

在八件同類品種中,天青色的只有一件,品質亦不如該次成交的品質高。值得注意的是,鈞窯的藍色(天青),並不是自身的藍。它來自釉層跟光的一個光學反射效果,只有藍色的光波被反射:瑞利散射(Rayleigh scattering),這也是為什麼天空是藍色的,這種對雨過天青的理解,從科學上的契合度也是近乎完美。

哈佛大學博物館

銘文器物

重華宮

The Palace of Double Glory

海棠盆

鐘型盆

養心殿

The Hall of Mental Cultivation

菱口盆

花口盆

方盆

建福宮

The Palace of Estalibhed Happiness

菱口盆

花口盆

哈佛大學這批1942年的捐贈,是研究官鈞年代的寶庫,共藏有渣鬥8件,其他各式花盆以及底座43件,共51件之巨量。

不管年代是宋代還是明代,這批器物無疑是帝王的珍寶,他們在乾隆人生的各個階段:凝暉堂時期、養心殿時期、寧壽宮時期都扮演著取悅帝王的精神支撐,是帝王文人情懷的一個寄託,在微縮自然中的情感歸宿。

ESKENAZI先生在2013年的展覽中,特地邀請了著名花藝大師Sumie Takahashi為兩件鈞窯創作了花藝,考究之極,至今仍是我們能看到的最好的對凝暉堂和帝王花圃的想象。

This 1942 donation from Harvard University is a treasure trove for the study of the Official Jun period, with a total of eight jardinières and 43 other assorted flowerpots and pedestals, making a huge collection of 51 pieces.

Regardless of whether the date is the Song or Ming dynasty, these objects were undoubtedly treasures of the emperor, and they played a role in pleasing the emperor's spirit at various stages of his life: during the period of the Hall of Concentration, the period of the Hall of Yangxin, the period of the Palace of Ningshou, and as a spiritual support for the emperor's literati sentiments, an emotional home in the miniature nature of the emperor.

For his 2013 exhibition, Mr ESKENAZI invited Sumie Takahashi, a renowned floral artist, to create floral arrangements for the two pieces of Junjun kiln, which are so elaborate that they are still the best imaginings of the Ningshutang and the Imperial Flower Garden that we can see.

Comments