Incense Notes | Incense and Prejudice in Yamanoue Sōji-ki, On Named Incenses and Historical Bias

- SACA

- Jan 20

- 11 min read

Shino-ryū Kodo: The Celebrated Incense “Ranjatai,” preserved at Shōin-ken of the Shino school of incense

By Allen Wang (Qiusheng Wang)

Chapters 18 to 20 of Yamanoue Sōji-ki are devoted to matters relating to incense. These passages should not be read as a mere catalogue of fragrance names; rather, they constitute a connective thread linking temples, the Ashikaga shogunate, tea practitioners, and renowned incense connoisseurs. Beginning with entries such as Taishi and Tōdaiji, and continuing through the ten principal incenses and the six later additions, these names were not bestowed on the basis of olfactory pleasure. Instead, they are deeply embedded in concrete historical contexts—temples such as Hōryūji and the Shōsōin, shogunal pilgrimages, ritual cuttings of precious woods, and systems of oral transmission and secrecy. Each name encapsulates a specific historical situation.

Yamanoue Sōji was a tea practitioner from Sakai active in the late Sengoku period, and one of the direct disciples of Sen no Rikyū. Among extant historical sources, he can be clearly identified as a close follower of Rikyū. He is best known for recording and commenting on Rikyū’s tea practice, and his work, Yamanoue Sōji-ki, has become an indispensable source for understanding both Rikyū’s thought and the practical realities of tea culture in the late sixteenth century. Historically speaking, Sōji’s significance rests primarily on his role as a witness and recorder, rather than as a founder of a lineage or school in his own right.

In practice, Sōji was indeed conversant with the central domains of the sukiya world of his time, including tea and incense, and possessed a substantial degree of hands-on experience with famous objects, utensils, and incense practices. Born in 1527 and executed in 1590, Yamanoue Sōji was a direct disciple of Sen no Rikyū and is known today chiefly through Yamanoue Sōji-ki. His core identity may be summarized as follows: a participant in tea gatherings, a faithful recorder of Rikyū’s ideas, and an insider-observer of the cultural milieu of the Azuchi–Momoyama period. He was neither a hereditary incense master (iemoto) nor the creator of an incense system.

What deserves particular emphasis is the pronounced extremity of Sōji’s temperament and conduct, as reflected in historical sources. His judgments of people and events are often blunt, uncompromising, and conspicuously lacking in sensitivity to the surrounding political environment and power structures. In contrast to Rikyū—who demonstrated remarkable restraint and a finely calibrated sense of proportion while operating under intense political pressure—Sōji appears to have lacked comparable mechanisms of self-regulation. Ultimately, his words and actions became entangled with politics, leading to his execution by beheading. This outcome, in itself, functions as a historical commentary on his character and his manner of engaging with the world.

I. On the Historical Status of the Shino School and the Problem of Misreading

In the original text of Yamanoue Sōji-ki, the roles of the Sanjō and Shino families in the early modern period are reductively characterized as having “degenerated into formalism due to the scarcity of genuine incense.” By citing remarks attributed to Tatebe Takakatsu, the text further suggests that judgments based on Shino-family written formats are inherently unreliable. Such assertions are highly context-dependent. When reproduced without critical qualification, they amount to an unfair assessment of the Shino school and, more broadly, reveal inaccuracies in Yamanoue Sōji’s understanding of incense culture. These inaccuracies not only expose the limits of Sōji’s own knowledge but also underscore the historical reality of information asymmetry in the late Sengoku period. Taken at face value, such claims directly undermine the overall credibility of Yamanoue Sōji-ki as a historical source.

It must first be emphasized that since its formation in the late Muromachi period, the Shino school has maintained an unbroken lineage for more than five centuries. Its transmission was never dependent on the possession of a particular cache of famous incense woods, but rather on a fully developed system of incense practice—encompassing institutional structures, technical vocabulary, and embodied modes of performance.

The Shino school was by no means a later, hollow construct. It inherited its authority from the Ashikaga shogunal house, preserved a recognized corpus of sixty-one named incenses, and has long been acknowledged as a lineage associated with the custody of Ranjatai. In light of these facts, portraying the Shino school as a purely formalistic arbiter reliant solely on written manuals is clearly at odds with historical evidence. Sōji’s remarks should instead be understood as the product of a highly subjective and polemical stance rooted in the specific personal and political circumstances of the late Sengoku period, rather than as a definitive judgment on the legitimacy of incense lineages.

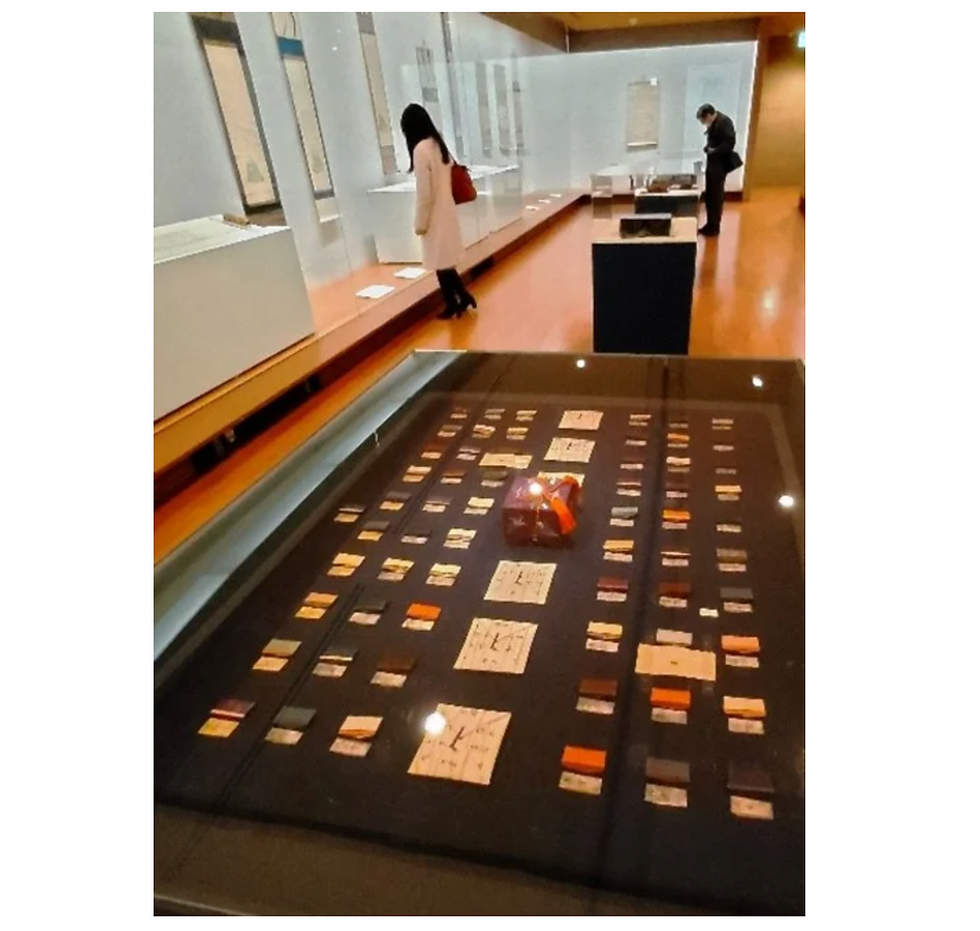

Shino School of Incense, 500th years anniversary exhibition at the Hosomi Musuem, Kyoto

This institutional continuity was vividly illustrated in the special exhibition “The Lineage of the Shino School of Incense: Commemorating the 500th Anniversary of the Death of the First Shino Sōshin” held at the Hosomi Museum. According to the established historical record, the first-generation master Shino Sōshin, acting under the orders of Ashikaga Yoshimasa, systematized and classified 180 named incenses collected by Sasaki Dōyō, the so-called “Basara daimyō.” From these, he further refined a selection drawn from sixty-six incense woods formerly held by Sanjōnishi Sanetaka, ultimately codifying the system of sixty-one celebrated incenses. Among them, Tōdaiji occupies a particularly eminent position, having been cut from the Shōsōin treasure Ranjatai—arguably the most renowned incense in Japanese history.

Each incense piece was wrapped in gold- or silver-foil sachets inscribed with its name, further encased in layers of differently colored paper, and grouped into six bundles. In the exhibition, these layers were ceremonially unwrapped and displayed sequentially. According to tradition, the name Tōdaiji itself was derived from hidden characters embedded within the three characters of Ranjatai.

II. On Rikyū, Shino Ryu, and the Problem of “Omniscient Narratives”

Even more problematic is the narrative model implicitly embedded in the original text—one that suggests that only a single figure, Sen no Rikyū, “understood everything,” while all others were either mere formalists or narrowly specialized technicians.

Chapter 20 of Yamanoue Sōji-ki, “Masters of Incense,” asserts that in Sakai, only three individuals—Sen no Sōeki (Rikyū), Tennōjiya Sōgyō, and Yamanoue Sōji himself—were fully versed in the entirety of incense knowledge, with only a handful of counterparts in Kyoto, conspicuously excluding Shino Sōshin. In this formulation, Sōji himself is elevated to the status of an all-knowing authority.

It is essential to note that Yamanoue Sōji-ki was not authored directly by Sōji. Rather, it is a posthumously compiled record of his words and actions, assembled by disciples and members of the tea community. While the text possesses undeniable documentary value, it must be read within the context of its textual formation and the broader process of Rikyū’s posthumous canonization.

From both chronological and institutional perspectives, the claim that only a few individuals “understood incense in its entirety” is untenable. First, it is well established that Sen no Rikyu was indeed an important learner within the Shino school system. Records of discipleship and related documentation attest that he studied under Shino lineage masters. What Rikyū inherited was not a nascent or incomplete tradition, but a mature and well-articulated system. To portray him as a solitary figure who independently “mastered all of incense culture” is more plausibly a product of later hagiographic embellishment.

This process of deification has obscured the historical fact that Rikyū himself was a disciple of the Shino school. Casting him as the singular repository of universal knowledge not only erases centuries of institutional accumulation within the Shino lineage, but also distorts Rikyū’s actual historical position. His significance lies precisely in his ability to exercise discernment and restraint within an existing framework, not in standing above or outside all systems.

A related strand of incense discourse appears in the text known as The Ten Virtues of Incense, traditionally attributed to the Northern Song poet Huang Tingjian. The virtues described—such as sharpening the senses, purifying body and mind, and alleviating loneliness—bear striking resemblance to what is now termed aromatherapy. The list of figures associated with this discourse is notable, including Hosokawa Yūsai, Miyoshi Nagayoshi, Matsunaga Hisahide, Sen no Sōeki (Rikyū), Imai Sōkyū, Gamō Ujisato, Oda Uraku, and Hon’ami Kōetsu. Tracing these networks further reveals an even wider constellation of well-known historical actors.

Yamanoue Soji (1544–1590), a senior disciple of Rikyū, was known for his blunt and uncompromising temperament and once served as tea attendant to Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Following the Odawara Campaign, however, his words and conduct antagonized Hideyoshi and brought him into political conflict. He was arrested, subjected to torture, and ultimately executed by beheading. While Sōji’s fate has often been framed as the result of unwavering loyalty to Rikyū, extant sources do not support such a simplistic causal explanation. Rather, his death reflects the vulnerability of cultural elites in the late Sengoku political environment and illuminates the persistent tension between tea culture and power politics. Notably, Hideyoshi ordered Sōji’s execution first, and only a year later compelled Rikyū to commit seppuku.

Yamanoue Sōji-ki

Selected Passages (Annotated Translation)

Chapter Eighteen

Hata Incenses (Ten Types of Incense Woods)

1. Taishi

The original wood (mokudokoro) is red sandalwood (akametandan).Within this original wood, those portions that have formed into sinking incense (jinkō) are designated as Taishi. As this incense was a treasured object of Hōryūji in Yamato Province (present-day Ikaruga, Nara), it was named after Prince Shōtoku.

2. Tōdaiji

The original wood is kyara, an incense of unparalleled renown under Heaven. It is said that during the lifetime of the Kubō (Ashikaga shogun), on the occasion of a pilgrimage to Nara (a visit to Kasuga Shrine), a square piece measuring one sun was cut from this incense wood (in fact, this was done by Ashikaga Yoshimasa in the ninth month of Kanshō 6).Later, when Oda Nobunaga visited the Shōsōin in the third month of Tenshō 2, I too took part in the cutting and use of this incense—namely, the Ranjatai of Tōdaiji.

3. Shōyō

The original wood is said to be the kawame (outer skin) of Ranjatai.Its name may derive from the notion of “leather-like wandering” (kawa shōyō).

4. Yoshino

The original wood is said to be the “hull” (funami) of the Ranjatai of Tōdaiji.

5. Nakagawa

One account holds that its original wood is Manaban.

6. Furuki

The original wood is Rakoku, specifically the portions that have formed into sinking incense.

7. Kōjin (“Red Dust”)

The original wood is kyara, a celebrated incense comparable to the Ranjatai of Tōdaiji.Its fragrance is particularly distinguished by its exceptional furi—the dynamic rise and modulation of scent.

8. Hanatachibana

Only the name survives; the original wood is unknown.

9. Hanabashi

The original wood is Manaka.That both Nakagawa and Hanabashi, belonging to the Manaban/Manaka category, should be included among the ten named incenses is truly astonishing, attesting to their exceptional status.

10. Yatsuhashi

The original wood is Rakoku.Although derived from the same category as Furuki, its furi exhibits especially intriguing variations.

11. Hokekyō (“Lotus Sutra”)

The original wood is kyara.An older account states that each bu (approximately 0.375 grams) of this incense was valued at eight kan of gold, hence the name likening it to the eight fascicles of the Lotus Sutra.This explanation, however, is no longer commonly accepted.

Each of the above incenses is further accompanied by detailed oral transmissions, to be taught separately.

Chapter Nineteen

Six Additional Incenses

1. Onjōji

The original wood is kyara. As its value rivals that of the Ranjatai of Tōdaiji, it was named after Onjōji, the head temple of the Tendai Jimon lineage.

2. Ni (“Resemblance”)

The original wood is kyara, a first-rank incense. At the initial burning it resembles ordinary kyara, but in the middle and later stages gradually reveals a fragrance akin to Ranjatai, hence the name.

3. Omokage (“Reflection” / “Afterimage”)

The original wood is kyara. It bears the “semblance” (omokage) of the Ranjatai of Tōdaiji, particularly manifesting a sense of recollection (omosho) in the kaeshi (returning phase), and may be discussed together with Ni.

4. Butsuza

This incense is exceptionally intriguing and entirely distinctive in character.

5. Juzu (“Rosary”)

The original wood is kyara.Because its fragrance compels one to keep it constantly at hand, it is also known by this name.

6. Shōbu

The original wood is Rakoku.Although many famed Rakoku incenses exist, Shōbu stands at the very pinnacle of fragrance.

Beyond these, there are also so-called “Fifty Varieties of Incense,” bearing alternative names and diverse origins.However, when the incense master Tatebe Takakatsu sought instruction in the appreciation of named incenses from Sōeki (Sen no Rikyū), Tennōjiya Sōgyō, and myself, these sixteen named incenses alone were transmitted to him as secret teachings.

Chapter Twenty

Masters of Incense

In Sakai, those who fully comprehend incense practice in its entirety are limited to Sen no Sōeki, Tennōjiya Sōgyō, and Yamanoue Sōji alone. In Kyoto as well, there are only a few such individuals.

1. Tatebe Takakatsu

Foremost authority in the identification of famed incense woods.He possessed Kōjin (“Red Dust”), one of the Ten Incenses, and treasured it throughout his life.He died in Tenshō 6 (1578).

2. Gion Yamamoto

Holder of the named incense Miyako. It is said that Miyako is a concealed name for Tōdaiji among the Ten Incenses.

3. Chikuon’in

Holder of Yatsuhashi, one of the Ten Incenses.

4. Kawamura Dōyo

Holder of Ni, one of the Six Additional Incenses.He died before Tenshō 6.

5. Manase Dōsan

Though not famed as an incense connoisseur, he possessed one kan of the transmitted Ten Incenses’ Ranjatai.He was a disciple of Morito, a monk of the Rinzai Zen sect at Shōkokuji.His Ranjatai was a gift from the Kubō and was widely known; it alone was a truly genuine specimen.Although other named incenses are scattered across various places, few are genuinely trustworthy.Only those recognized in common by the above-mentioned Kyoto masters may be regarded as reliable.

The Sanjō family among the court nobility and the Shino family among the warrior class have long served as hereditary authorities in incense authentication.In recent times, however, owing to the extreme scarcity of genuine incense, they have fallen into formalism.Tatebe Takakatsu even remarked that if an incense pouch bears the written format of the Sanjō or Shino families alone, this may in fact serve as proof that it is not a true named incense.

Matters of incense may also be consulted with Jōniku Sōchū.

As for the finer points of incense identification, these must again be transmitted orally.

End of selected passages from Yamanoue Sōji-ki.

Conclusion

The incenses listed in this study—whether among the “Ten Incenses” or the “Six Additional Incenses”—together constitute a judgment system grounded in direct experience with actual incense woods, one that has accumulated over a history of more than five centuries. This system encompasses diverse categories of source material, including kyara, rakoku, manaka, manaban, and red sandalwood. It includes both a lineage of celebrated incenses centered on the Ranjatai of Tōdaiji and cases in which distinctions arising from different sections of the same wood—variations in resin concentration, internal structure, and the temporal modulation of fragrance—became objects of refined appreciation, as exemplified by Kōjin (“Red Dust”). These names were not arbitrarily assigned; rather, they represent a high level of abstraction derived from repeated sensory engagement with layers of scent, rhythms of transformation, and embodied practices of incense listening.

The value of an incense name lies not in the breadth of its circulation, but in whether it can be substantiated through actual olfactory experience. As genuinely ancient incense woods have become increasingly scarce, later generations were compelled to formalize and institutionalize what had once been transmitted through lived practice. This process of formalization does not imply that the original judgments lost their validity. On the contrary, it is precisely through the preservation of these names and classificatory schemes that we are still able today to trace the historical heights once reached in the understanding of fragrance.

From this perspective, what is preserved through these incense woods is not merely a set of famous names, but an entire mode of thinking: a method for apprehending scent, comparing fragrances, and discerning authenticity. It is in this methodological legacy that their true significance resides.

Although the record attributed to Yamanoue Sōji was compiled posthumously and contains unmistakable biases toward certain lineages and authority structures, its sharpness of tone and proximity to the events of its time endow it with a vivid sense of immediacy and tension. These qualities, rather than diminishing its value, render it an indispensable historical source.

What requires adjustment, therefore, is not the text itself, but the manner in which it is used. Yamanoue Sōji-ki may serve as a guide and a point of departure, but it should not be treated as a final arbiter. Any judgment concerning the authenticity of named incenses, the legitimacy of lineages, or the authority of institutional systems must be corroborated through multiple sources and re-situated within the political, religious, and cultural structures of the period. Only through repeated verification within a clearly defined historical framework can what is reliable be affirmed, and what is questionable be properly corrected.

The author, Allen Wang (Qiusheng Wang), is the founder of the SACA Society, an assistant instructor in the Urasenke school of tea, and a disciple of the Shino school of incense.

Comments